WORDS: DAVEY COOMBS

PHOTOS: SIMON CUDBY

WORDS: DAVEY COOMBS

PHOTOS: SIMON CUDBY

n February 13, 2018, Tickle finished fifth at the San Diego Supercross. Afterward, he was one of ten riders tested by the FIM as part of their anti-doping procedures. Six weeks later, just before the press-day ride at the Minneapolis SX, Tickle received an email from the FIM legal department telling him he was provisionally suspended, effective immediately. He had tested positive for the stimulant methylhexaneamine, which is banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). It’s the same stimulant that Australian road racer Anthony West tested positive for in 2012. West was at first suspended by the FIM for one month, but then WADA asked for a harsher sentence before the Court of Arbitration for Sports (CAS). Despite an appeal by West, he was ultimately suspended for 18 months.

Tickle says he never saw it coming, and his search for answers began immediately. “I read [the email] and I was like, you’ve got to be kidding me. I called the team, I called Aldon [Baker], I called everybody,” he says. As the stadium’s parking lot filled up with big rigs, Tickle flew home to get himself tested in a lab. He says he tested clean and in accordance with the WADA code. He had the supplements he was taking at the time tested; they also checked out.

n February 13, 2018, Tickle finished fifth at the San Diego Supercross. Afterward, he was one of ten riders tested by the FIM as part of their anti-doping procedures. Six weeks later, just before the press-day ride at the Minneapolis SX, Tickle received an email from the FIM legal department telling him he was provisionally suspended, effective immediately. He had tested positive for the stimulant methylhexaneamine, which is banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). It’s the same stimulant that Australian road racer Anthony West tested positive for in 2012. West was at first suspended by the FIM for one month, but then WADA asked for a harsher sentence before the Court of Arbitration for Sports (CAS). Despite an appeal by West, he was ultimately suspended for 18 months.

Tickle says he never saw it coming, and his search for answers began immediately. “I read [the email] and I was like, you’ve got to be kidding me. I called the team, I called Aldon [Baker], I called everybody,” he says. As the stadium’s parking lot filled up with big rigs, Tickle flew home to get himself tested in a lab. He says he tested clean and in accordance with the WADA code. He had the supplements he was taking at the time tested; they also checked out.

“But more recently, the compound has become a popular dietary supplement and is found in strength-conditioning and powder drinks, which help with training,” the newspaper adds. “The other problem with methylhexaneamine is that it isn’t always identified on the product.”

To this day, Tickle denies knowingly ingesting the banned substance, and he’s had all of the nearly dozen supplements he was taking at the time tested. He’s also been waiting in limbo for the FIM to get to his case, though there’s a line—privateer Cade Clason has been waiting in it since March 2017, when he tested positive for Adderall, the same medication that tripped up James Stewart and cost “the fastest man on the planet” 16 months in the twilight of his career.

“In my position, there’s not much I can do, and that’s what makes this so bad,” Tickle says of his growing frustration with the process. “I don’t really have any force behind me to tell them what to do or how to do it.”

“But more recently, the compound has become a popular dietary supplement and is found in strength-conditioning and powder drinks, which help with training,” the newspaper adds. “The other problem with methylhexaneamine is that it isn’t always identified on the product.”

To this day, Tickle denies knowingly ingesting the banned substance, and he’s had all of the nearly dozen supplements he was taking at the time tested. He’s also been waiting in limbo for the FIM to get to his case, though there’s a line—privateer Cade Clason has been waiting in it since March 2017, when he tested positive for Adderall, the same medication that tripped up James Stewart and cost “the fastest man on the planet” 16 months in the twilight of his career.

“In my position, there’s not much I can do, and that’s what makes this so bad,” Tickle says of his growing frustration with the process. “I don’t really have any force behind me to tell them what to do or how to do it.”

he Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme, or FIM, is the governing body for international motorcycle sport, with affiliated national federations (including the AMA) in more than 100 countries. Ever since 2002, the AMA Supercross tour has been co-sanctioned by the FIM and designated with world championship status, despite the fact that the races are held exclusively in the United States (with the exception of occasional rounds in Toronto). This is the leftover splatter from the war between AMA Pro Racing and then-SX promoter Clear Channel over the rights to supercross. Even though that war ended and the promoters and the AMA got back together, the agreement with the FIM remained in place. It was decided that the rulebook would be almost entirely written by the AMA, with two exceptions: noise and fuel, the latter of which caused lots of headaches about 15 years ago when both Chad Reed and Ricky Carmichael were penalized for having too much lead in their fuel.

The FIM has a sporting code that governs competition, a medical code, an environmental one, and a disciplinary and arbitration code. A decade ago, the FIM decided to join forces with WADA for anti-doping in all of their world championship events. That anti-doping code has now tripped up three supercross athletes: Stewart, Clason, and Tickle. In all three cases, the FIM seemed to slow-walk the due process usually afforded to athletes, as time is of the essence when you have a relatively short career span.

While three AMA Supercross riders have been suspended for using banned substances, there have been no known positive tests for MXGP, which raises the question: Is there a baked-in bias against AMA-based riders within the FIM? Well, what are the statistical possibilities that, from a group of 90 riders entered in the 2018 FIM Motocross of Nations at RedBud, eight were randomly selected for fuel testing, and of those eight, all three members of Team USA were among them? Answer: 1 in about 949,000. That might make sense if you’re Broc Tickle and dealing with them, but it doesn’t make sense to rank-and-file members of the AMA and fans of AMA Supercross, who have seen a lot of FIM overreach throughout the years.

he Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme, or FIM, is the governing body for international motorcycle sport, with affiliated national federations (including the AMA) in more than 100 countries. Ever since 2002, the AMA Supercross tour has been co-sanctioned by the FIM and designated with world championship status, despite the fact that the races are held exclusively in the United States (with the exception of occasional rounds in Toronto). This is the leftover splatter from the war between AMA Pro Racing and then-SX promoter Clear Channel over the rights to supercross. Even though that war ended and the promoters and the AMA got back together, the agreement with the FIM remained in place. It was decided that the rulebook would be almost entirely written by the AMA, with two exceptions: noise and fuel, the latter of which caused lots of headaches about 15 years ago when both Chad Reed and Ricky Carmichael were penalized for having too much lead in their fuel.

The FIM has a sporting code that governs competition, a medical code, an environmental one, and a disciplinary and arbitration code. A decade ago, the FIM decided to join forces with WADA for anti-doping in all of their world championship events. That anti-doping code has now tripped up three supercross athletes: Stewart, Clason, and Tickle. In all three cases, the FIM seemed to slow-walk the due process usually afforded to athletes, as time is of the essence when you have a relatively short career span.

While three AMA Supercross riders have been suspended for using banned substances, there have been no known positive tests for MXGP, which raises the question: Is there a baked-in bias against AMA-based riders within the FIM? Well, what are the statistical possibilities that, from a group of 90 riders entered in the 2018 FIM Motocross of Nations at RedBud, eight were randomly selected for fuel testing, and of those eight, all three members of Team USA were among them? Answer: 1 in about 949,000. That might make sense if you’re Broc Tickle and dealing with them, but it doesn’t make sense to rank-and-file members of the AMA and fans of AMA Supercross, who have seen a lot of FIM overreach throughout the years.

Dingman went on to explain that, in his opinion, the previous FIM administration was vindictive of members who sided with Viegas when he ran against Ippolito, and that included the AMA. So it should have come as no surprise that, soon upon taking over, Viegas cleaned house, including firing the FIM’s CEO, Steve Aeschlimann, as well as the deputy CEO and lawyer, Richard Perret—the man whose desk seemed to be where all of these cases stalled.

“Similar to the situation with James Stewart, these individuals were ultimately responsible for the mishandling of the suspension of Broc Tickle, for the presence of a banned substance,” Dingman alleged. “FIM Medical Director David McManus has taken all of the heat publicly for the FIM’s mishandling of Tickle’s case but the reality is that the blame rests squarely with the FIM attorney who prevented Tickle from getting the due process he should have been afforded.” Dingman added that the previous FIM administration’s “ineptitude” wasn’t limited to Tickle’s case, and that the first order of business now is “looking at these outstanding cases and getting them adjudicated.”

ne of the hot-button topics of an already intriguing 2019 season has been the question of whether riders and race teams can partner with cannabidiol-related companies. In case you haven’t heard, CBD oils are a byproduct of hemp, which is a form of cannabis. The CBD oil products in question don’t have THC—which is what gets people high—are believed to have many medicinal benefits, and are rapidly growing in popularity. Riders like Dean Wilson and Chad Reed already have personal sponsorship deals lined up with Ignite and cbdMD, respectively, and soon many more will,

Dingman went on to explain that, in his opinion, the previous FIM administration was vindictive of members who sided with Viegas when he ran against Ippolito, and that included the AMA. So it should have come as no surprise that, soon upon taking over, Viegas cleaned house, including firing the FIM’s CEO, Steve Aeschlimann, as well as the deputy CEO and lawyer, Richard Perret—the man whose desk seemed to be where all of these cases stalled.

“Similar to the situation with James Stewart, these individuals were ultimately responsible for the mishandling of the suspension of Broc Tickle, for the presence of a banned substance,” Dingman alleged. “FIM Medical Director David McManus has taken all of the heat publicly for the FIM’s mishandling of Tickle’s case but the reality is that the blame rests squarely with the FIM attorney who prevented Tickle from getting the due process he should have been afforded.” Dingman added that the previous FIM administration’s “ineptitude” wasn’t limited to Tickle’s case, and that the first order of business now is “looking at these outstanding cases and getting them adjudicated.”

ne of the hot-button topics of an already intriguing 2019 season has been the question of whether riders and race teams can partner with cannabidiol-related companies. In case you haven’t heard, CBD oils are a byproduct of hemp, which is a form of cannabis. The CBD oil products in question don’t have THC—which is what gets people high—are believed to have many medicinal benefits, and are rapidly growing in popularity. Riders like Dean Wilson and Chad Reed already have personal sponsorship deals lined up with Ignite and cbdMD, respectively, and soon many more will, as the recent Farm Bill signed into legislation will soon make these hemp products—again, the kind without THC—legal across the country (with restrictions and regulations).

But not soon enough for the level of comfort required for Feld or the AMA or MX Sports Pro Racing or even NBC to allow them to freely advertise their logos on the riders’ gear or race bikes. Because the laws haven’t changed completely in every state, at least in regard to CBD with THC, what’s legal in California is not necessarily legal right next door in Arizona. And because the TV signal does not stop at state lines, it was decided in February that no CBD-related sponsorship would be allowed in the pits or paddock—let alone on the track—in Monster Energy AMA Supercross. Both Wilson and Reed have had fun skirting the restrictions with clever logo covers, videos, social media posts with hashtags like #censored and #FreeIgnite, and just showing off the products away from the track. Come summer, things should be a little more lenient, as legal hemp-related logos will be allowed on team rigs and awnings and whatnot in the paddock—just not out on the Lucas Oil Pro Motocross racetracks. It’s a baby step that’s meant to allow the network, sanctioning body, and race promoters to allow this growing industry (pardon the pun) to continue to garner mainstream acceptance without the riders and race teams completely missing out on new fields of potential sponsorship revenue. ![]()

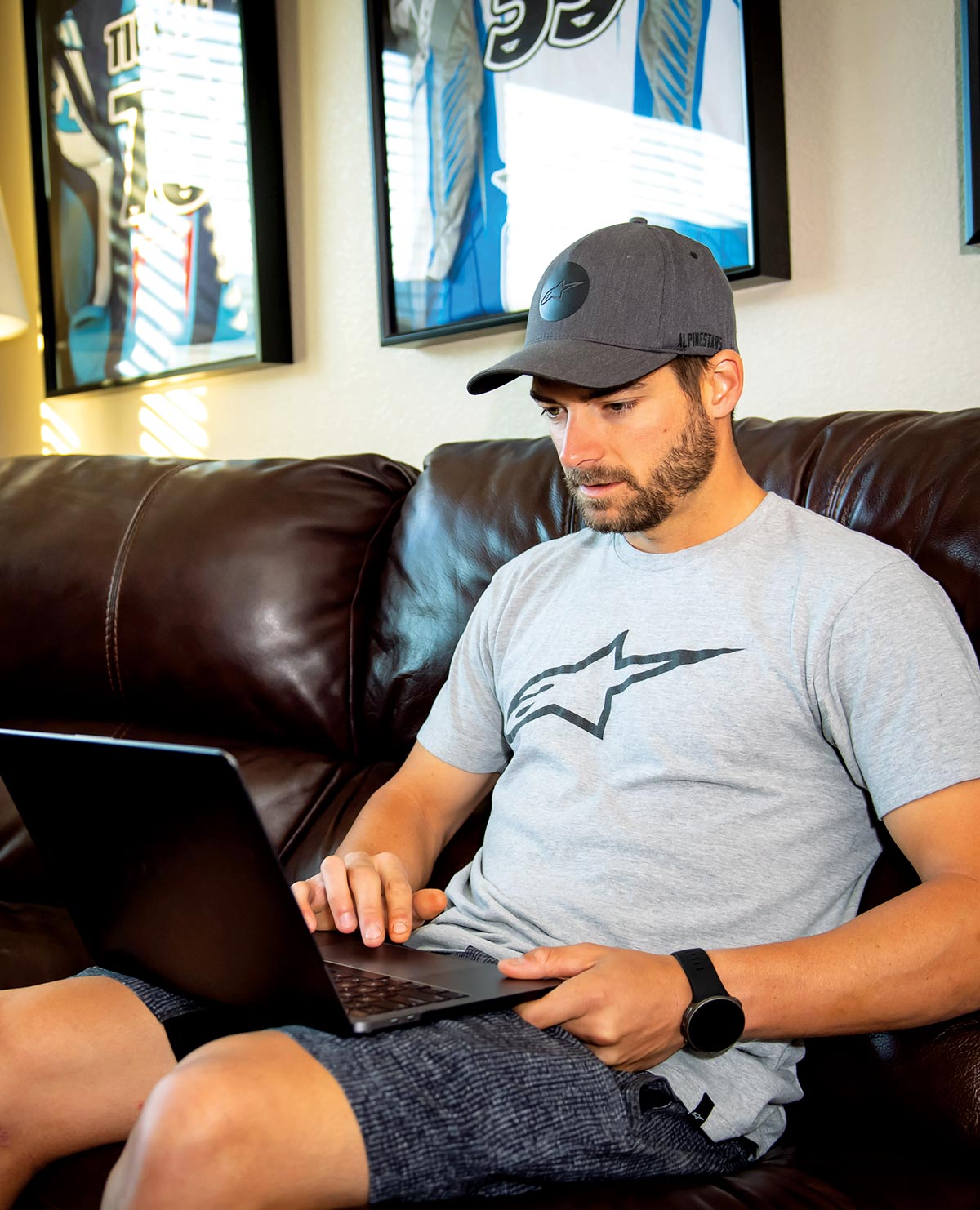

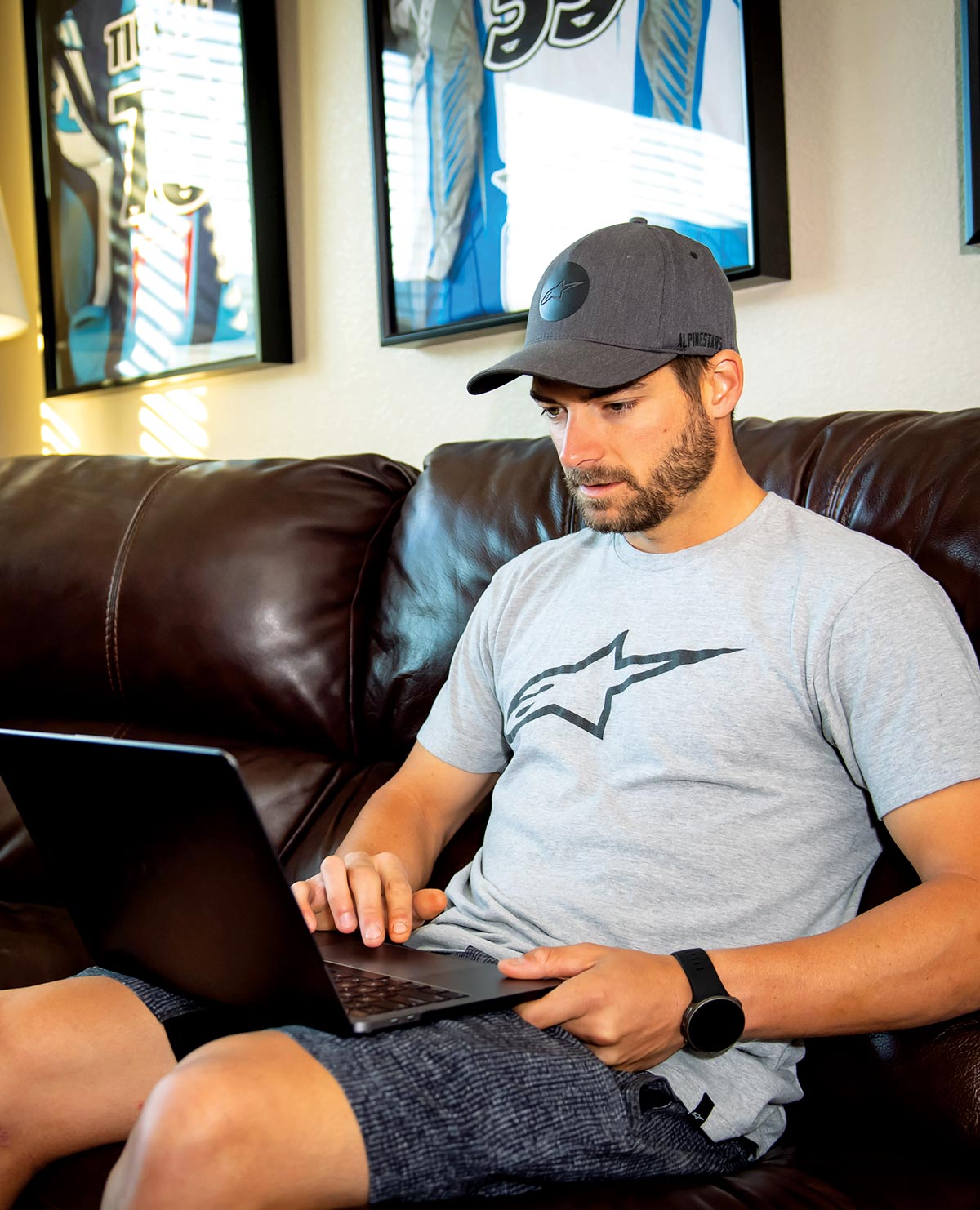

While he waits for his ultimate fate with the International Disciplinary Court, Tickle has been training on his mountain bike, doing riding schools, and staying abreast of his case online. He’s also attended several races as a spectator to visit old friends and keep his face out there.

While he waits for his ultimate fate with the International Disciplinary Court, Tickle has been training on his mountain bike, doing riding schools, and staying abreast of his case online. He’s also attended several races as a spectator to visit old friends and keep his face out there.

Broc Tickle is adamant that he has no idea how the banned stimulant methylhexaneamine got into his system. As a result, he could face as long as a four-year suspension when his case is finally settled, though something closer to 18 months could be in the offing, going by previous penalties.

Broc Tickle is adamant that he has no idea how the banned stimulant methylhexaneamine got into his system. As a result, he could face as long as a four-year suspension when his case is finally settled, though something closer to 18 months could be in the offing, going by previous penalties.

eanwhile, the highly respected Tony Skillington, a longtime advocate for riders in his nearly 30 years on the FIM’s motocross commission, was named CEO. When asked about Broc Tickle in a February 22 interview with Geoff Meyer of MX Large, Skillington replied, “All I can say in regard to Tickle, it is top of the list at the moment, and every effort is being made to bring this case to a conclusion.”

As for the AMA, Dingman was named a member of the FIM executive board, a powerful and influential role. However, he said he was not there to argue the facts of Tickle’s case or anyone else’s, but rather “to make sure these guys get a fair shake from the FIM and a much more efficient process. It’s up to the riders and trainers to educate themselves on the WADA code and know what they are eating and drinking at any given time.”

And here’s where things get really complicated for Tickle and his defense. As Americans, there is a legal assumption that we are innocent until proven guilty. But in the world of WADA and drug-testing, adverse analytical findings (i.e., failing a drug test) flip that script, and you begin as guilty—the smoking gun is already in your system. It’s then up to the athlete to explain how the banned substance got there, and the better the explanation and cooperation, the more likely the suspension will come down from the maximum of four years. In six previous cases involving positive tests for methylhexaneamine on the USADA website, the suspensions ranged from two years to just three months.

As we were going to print, on Wednesday, March 20—13 months after the initial positive test—Tickle was granted a hearing with the CDI to go over his case. Afterward, he was given a two-week window to provide further evidence and materials possibly related to how the banned substance got into his system. The wheels of justice were finally turning for him. Broc Tickle was still waiting for answers.