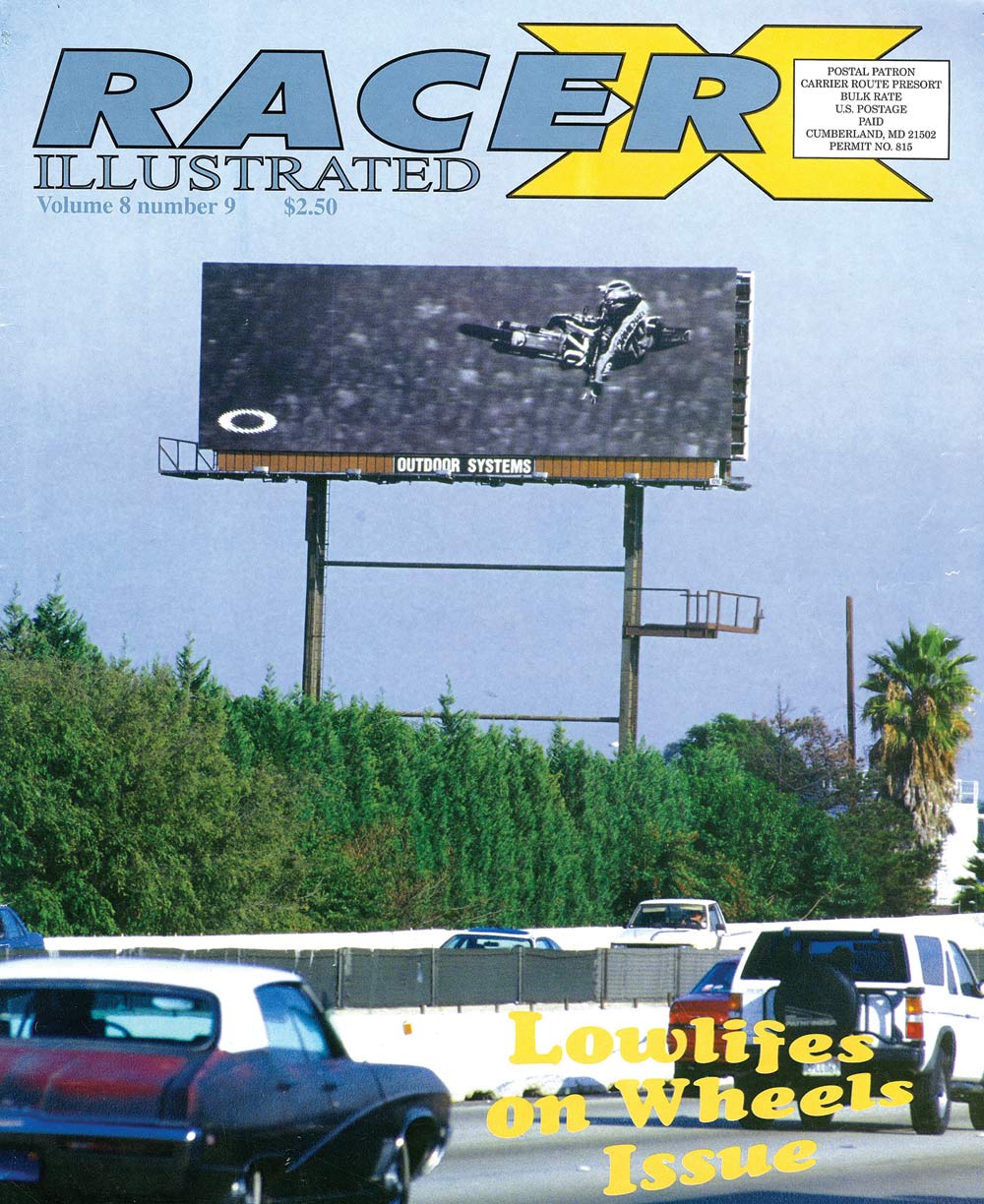

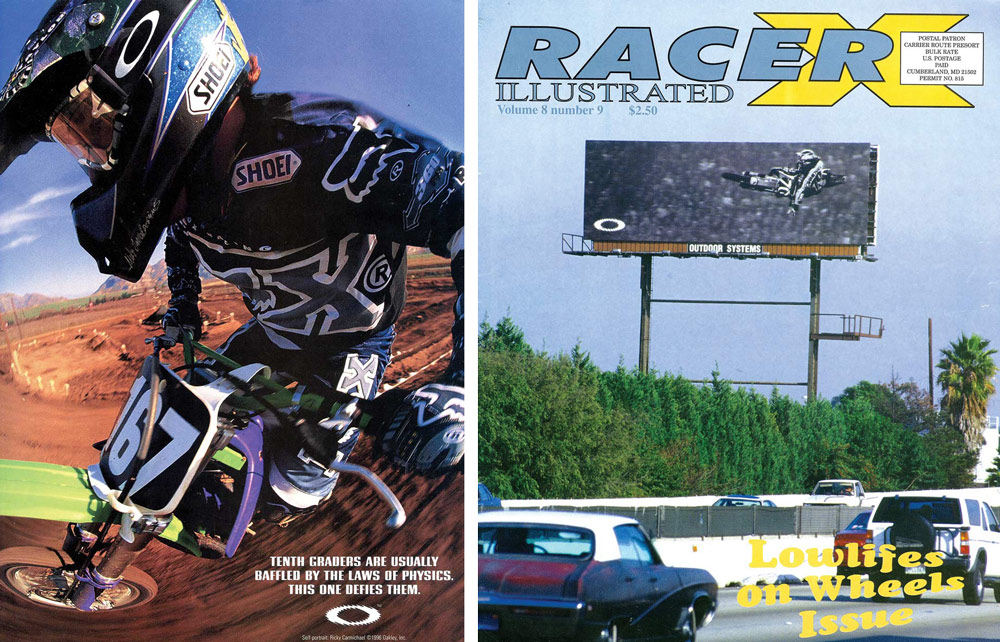

St. Onge approached the rack and pulled out Racer X Illustrated. The hair on his arms stood up; he felt his face get hot and his head spin trying to process the thoughts. His photo wasn’t really on the cover. Instead, the cover was a photo of his photo, which was . . . is that an Oakley advertisement? Is that a billboard?

St. Onge approached the rack and pulled out Racer X Illustrated. The hair on his arms stood up; he felt his face get hot and his head spin trying to process the thoughts. His photo wasn’t really on the cover. Instead, the cover was a photo of his photo, which was . . . is that an Oakley advertisement? Is that a billboard?

t. Onge didn’t ride his first motorcycle until his late twenties, around 1995. He fell in love with motocross and followed the sport on ESPN. A self-employed audio engineer/producer from the Buffalo area, he became interested in photography shortly after discovering dirt bikes. For Christmas 1996, he bought his wife a Canon Rebel G, a prosumer-grade 35mm camera, and soon found himself absorbed in photography manuals and trade journals. He studied the technical aspects of the equipment and craft and practiced every chance he got.

The next April, he cut through Canada to attend the Pontiac SX. He brought along the camera, a 75-300mm telephoto lens, and several 36-exposure rolls of Kodak Royal Gold 1000. He shot along the railing during afternoon practice but spent the evening in the lower bowl of the Pontiac Silverdome shooting from his seat. He believes he was in the 17th row.

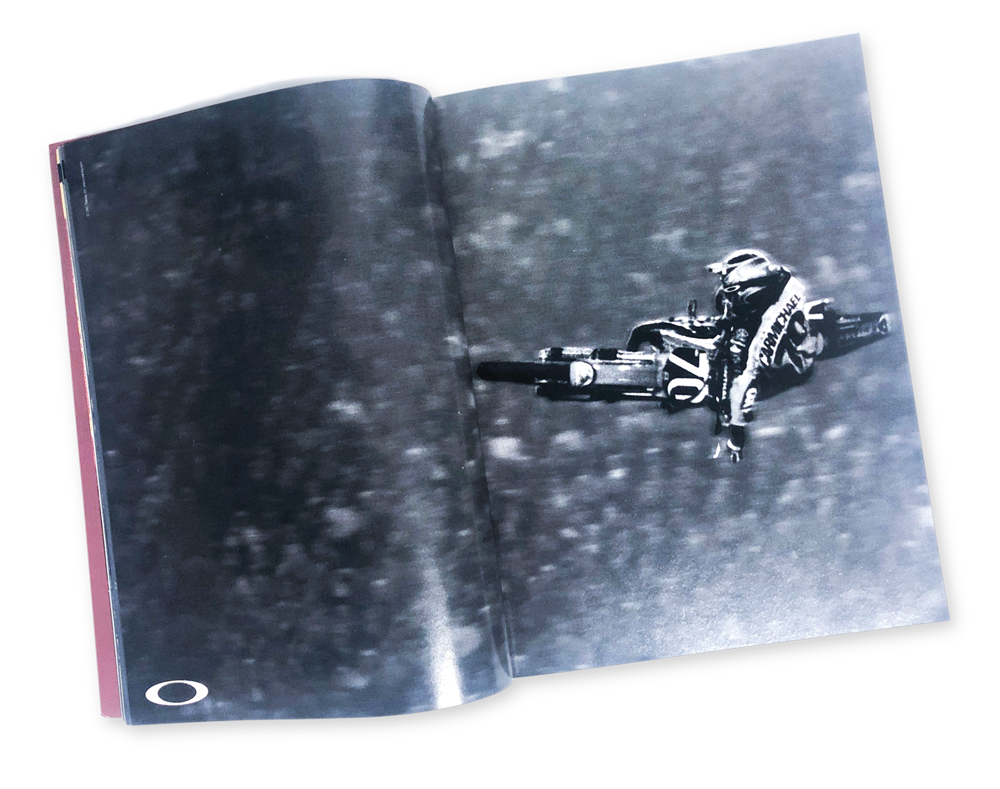

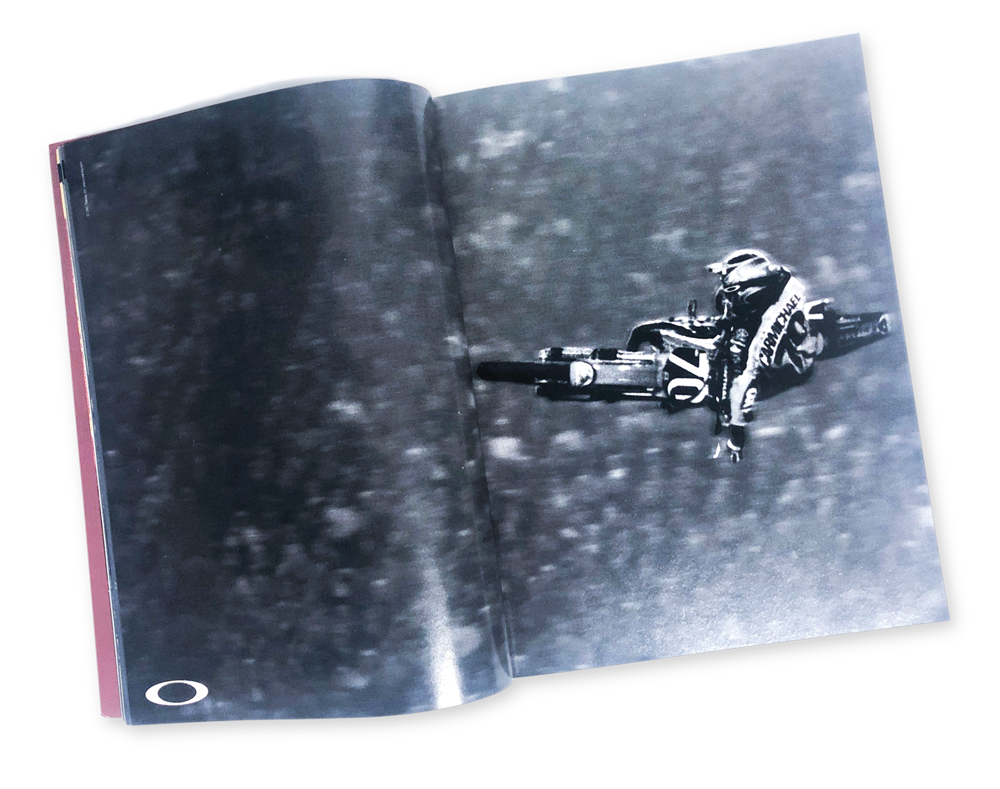

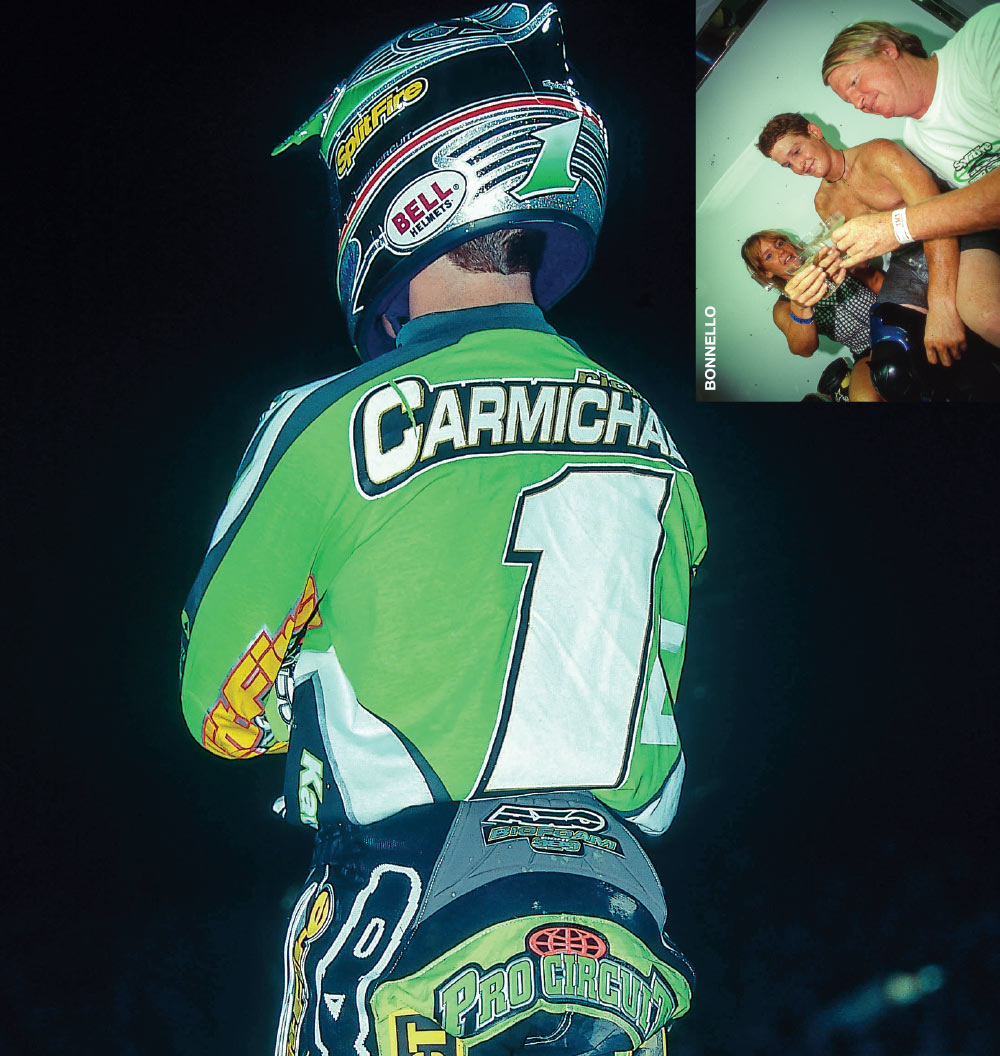

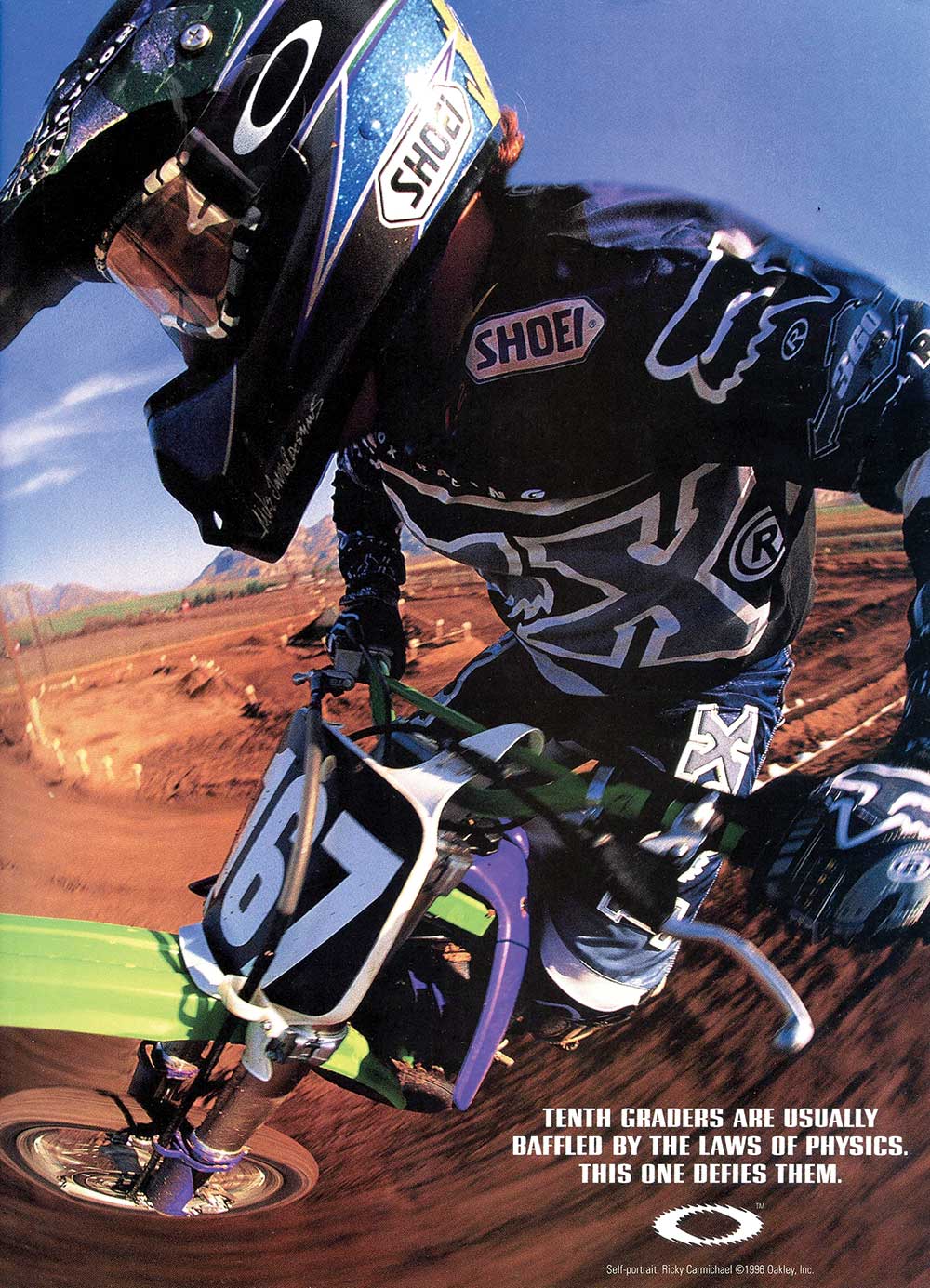

At the end of the second 125cc heat race, St. Onge followed Carmichael through the viewfinder as RC approached the finish line and–click–took exactly one photo of the kid in the air. Laying the bike completely flat after a heat-race win summed up Carmichael’s rookie season: completely unpredictable. Man, I think I might have got something there, St. Onge thought to himself. I think I might have got a good shot.

t. Onge didn’t ride his first motorcycle until his late twenties, around 1995. He fell in love with motocross and followed the sport on ESPN. A self-employed audio engineer/producer from the Buffalo area, he became interested in photography shortly after discovering dirt bikes. For Christmas 1996, he bought his wife a Canon Rebel G, a prosumer-grade 35mm camera, and soon found himself absorbed in photography manuals and trade journals. He studied the technical aspects of the equipment and craft and practiced every chance he got.

The next April, he cut through Canada to attend the Pontiac SX. He brought along the camera, a 75-300mm telephoto lens, and several 36-exposure rolls of Kodak Royal Gold 1000. He shot along the railing during afternoon practice but spent the evening in the lower bowl of the Pontiac Silverdome shooting from his seat. He believes he was in the 17th row.

At the end of the second 125cc heat race, St. Onge followed Carmichael through the viewfinder as RC approached the finish line and–click–took exactly one photo of the kid in the air. Laying the bike completely flat after a heat-race win summed up Carmichael’s rookie season: completely unpredictable. Man, I think I might have got something there, St. Onge thought to himself. I think I might have got a good shot.

At the end of the second 125cc heat race, St. Onge followed Ricky Carmichael through the viewfinder as RC approached the finish line and– click–took exactly one photo of the kid in the air.

At the end of the second 125cc heat race, St. Onge followed Ricky Carmichael through the viewfinder as RC approached the finish line and– click–took exactly one photo of the kid in the air.

“I’m lucky that I didn’t wreck,” Carmichael says. “I landed and I’m like, ‘I can’t believe I pulled that off.’”

A few days later, St. Onge sat in the parking lot of a Tops grocery store flipping through the stack of developed color 4×6 prints, the first images he’d ever shot at a race. While he had yet to develop the critical eye of a seasoned artist, he had genuine excitement for all of his photos. But then he stopped at the Carmichael shot.

“Okay, that’s pretty cool,” he said to himself in the parking lot.

he photo is perfectly timed. Carmichael is at peak pancake, the exact midpoint of his whip. The original (and uncropped) version has, depending on personal aesthetic tastes, more visual clutter. Carmichael is still the focus, but there’s so much else to see. The crowd is more discernible; facial expressions can’t be read, but actions can. Everyone sits at ease, focused on Carmichael. The white hole of flashbulb in the upper left corner indicates at least one other fan captured this exact moment as well. The bottom half of the photo is the stadium floor filled with piles of dirt and frumpy-looking hay bale covers and banners. Four of the five flaggers are craning their necks to look up at Carmichael. A photographer aims his lens upward, but not at a steep enough angle to shoot the winner. No one is holding up a camera phone.

“I got home and showed anybody that wanted to listen about my photo,” St. Onge says. “But that was about the extent of it.”

St. Onge already had plans to attend the next race, in Charlotte. He stuffed a small album full of his prints and now had an excuse to interact with the riders by showing them his photos. He got feigned excitement in North Carolina.

“Oh, that’s nice,’ they said, though most of the photos were crap in hindsight,” St. Onge admits. He saw Carmichael last, and when he handed over the print, the teenager lit up.

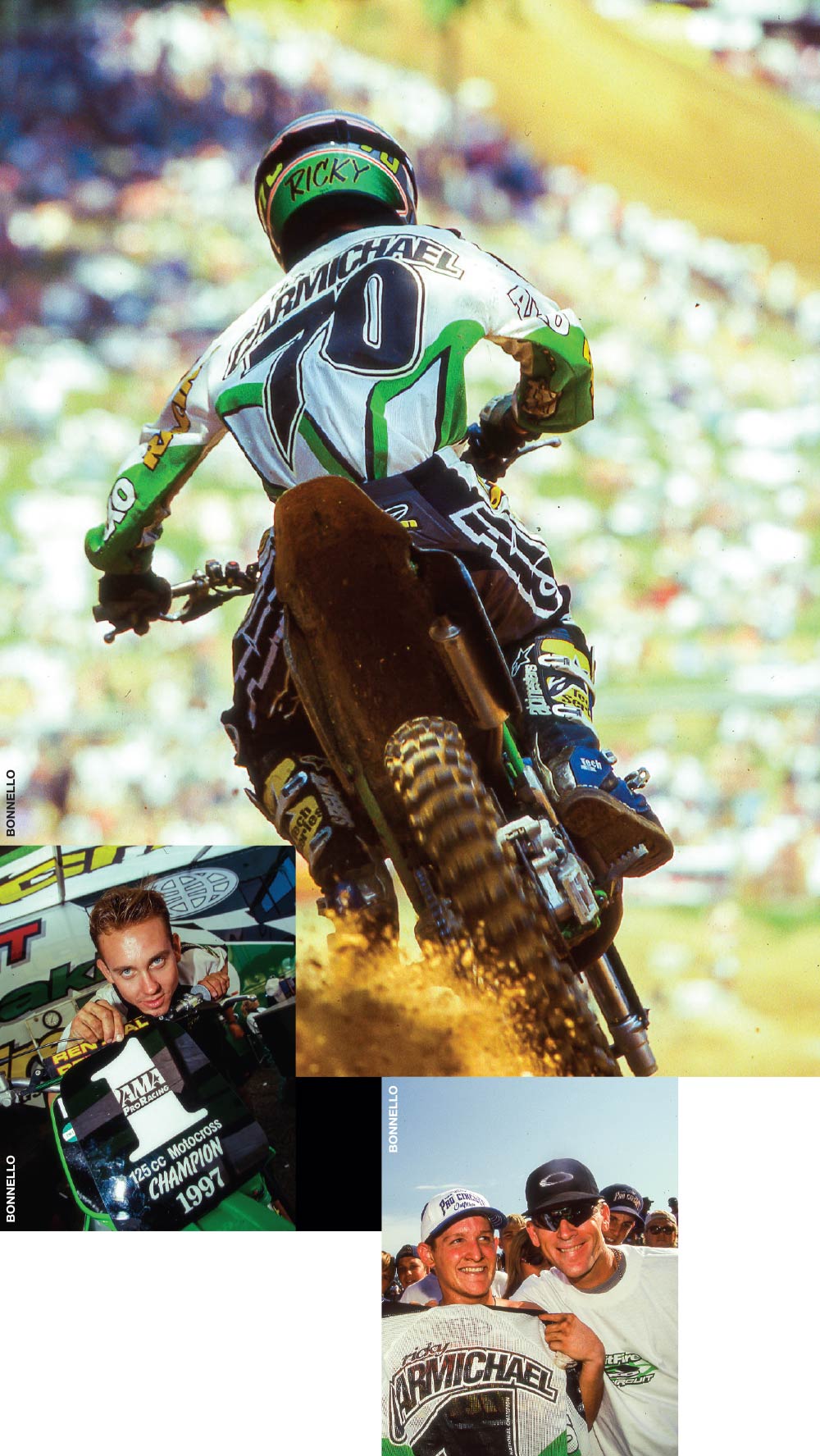

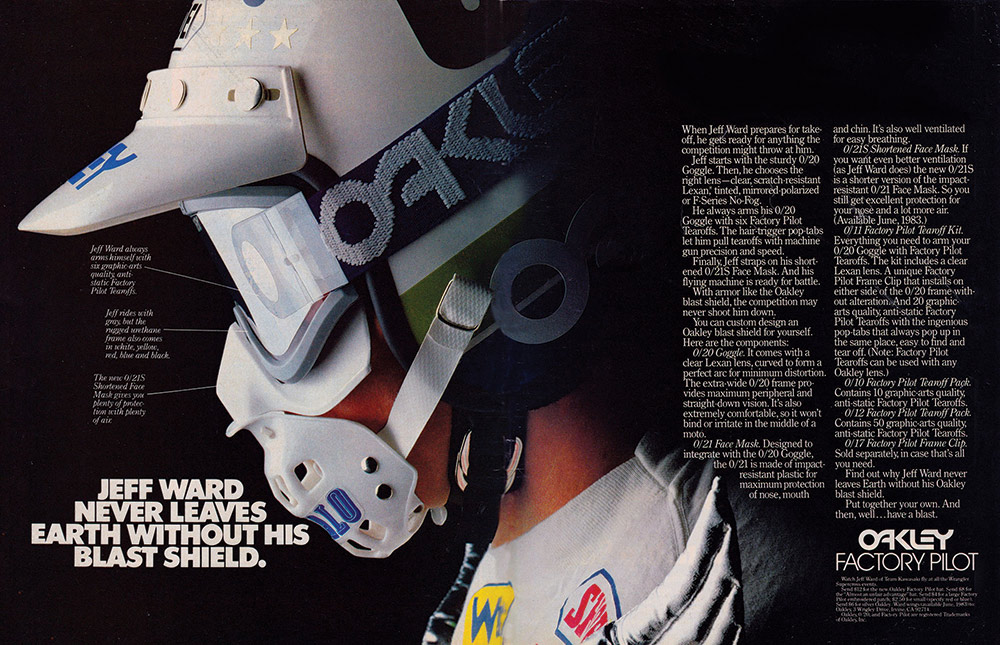

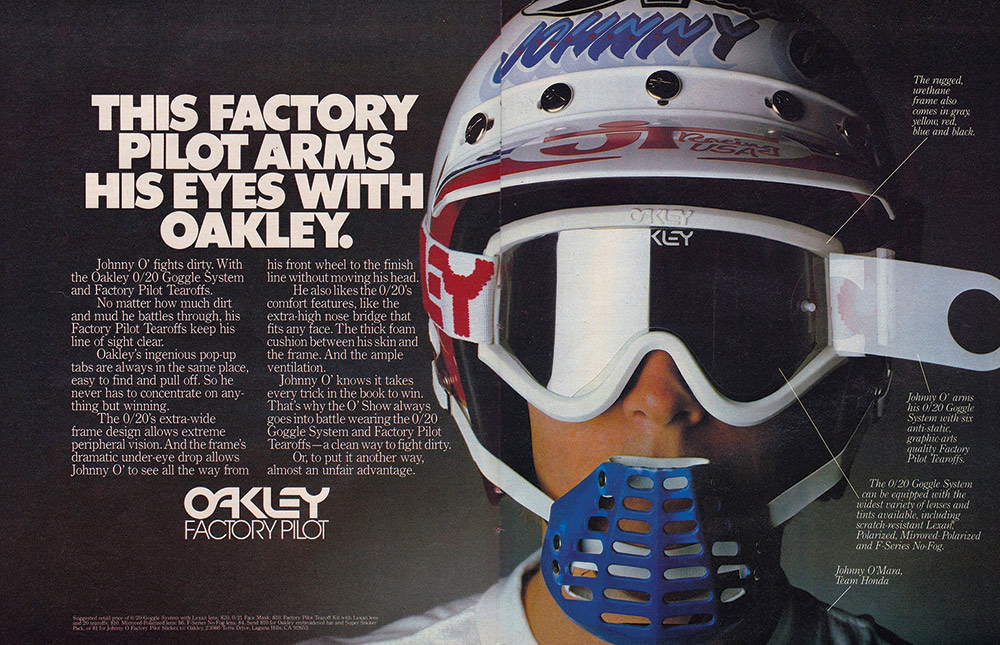

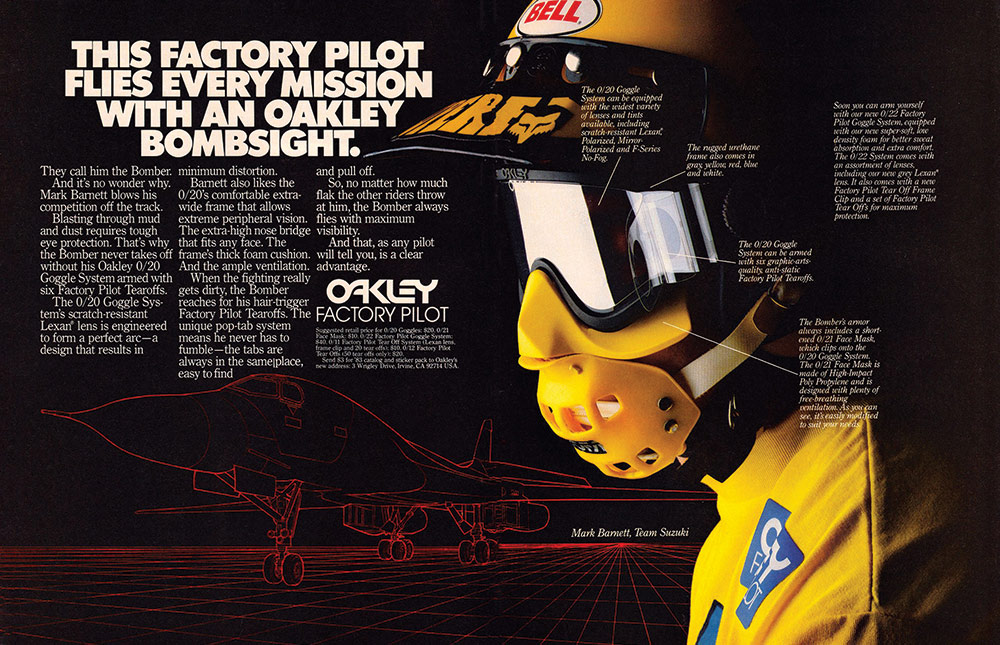

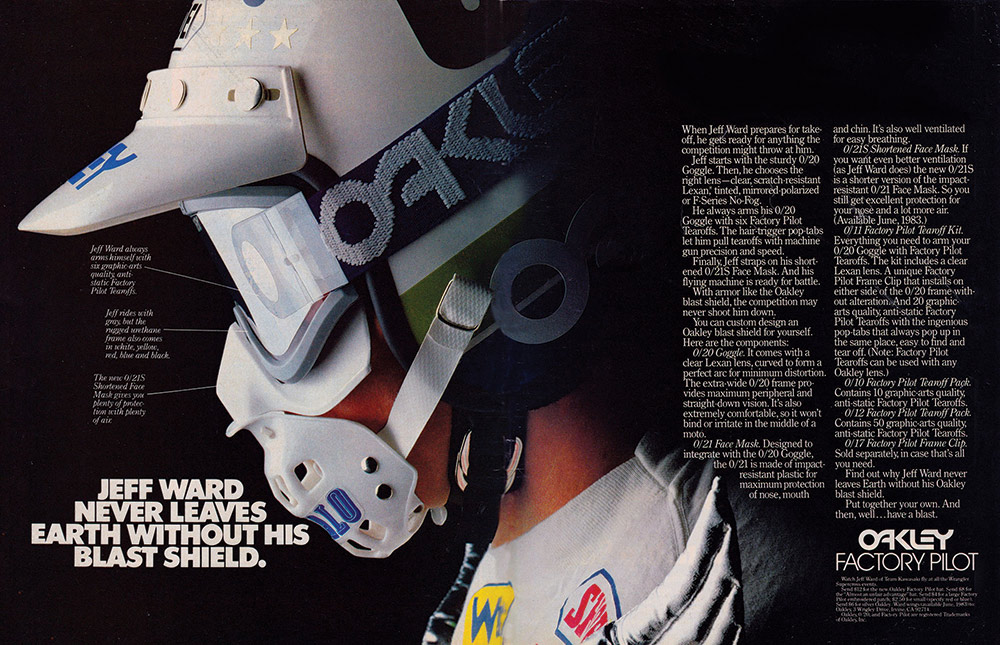

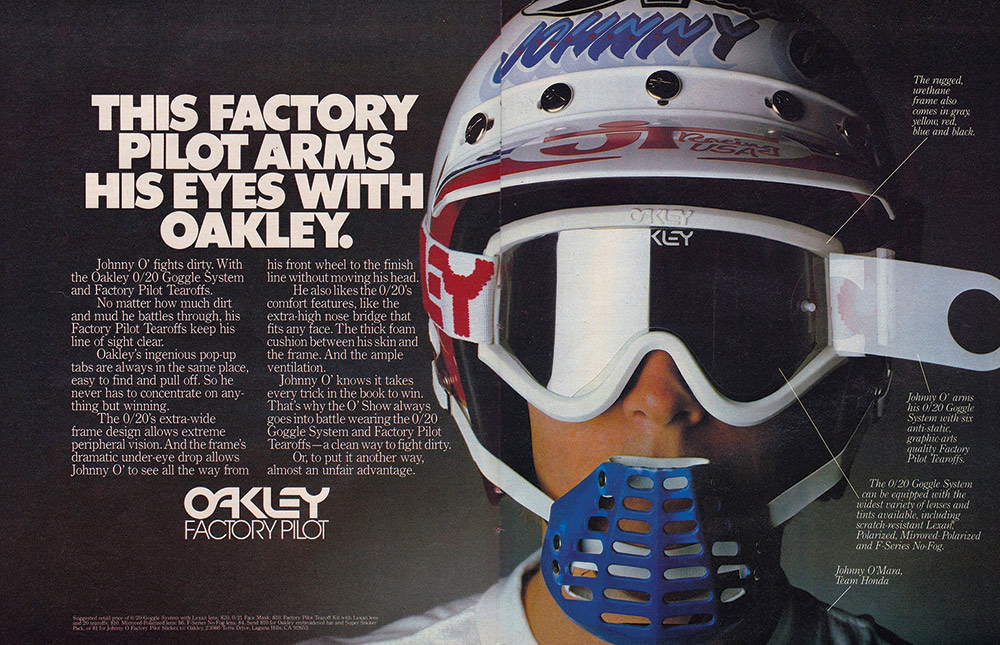

armichael won in Charlotte, the third victory of his rookie season. At some point that day, he showed the photograph to his mentor Johnny O’Mara and asked the 1984 AMA Supercross champ to take it back to Oakley, where he worked as motorcycle racing sports marketing manager, to make some color photocopies on the office printer. Ricky laughs about how corny this sounds today, but he literally just wanted something to tape up in his bedroom. Says Carmichael, “I think he brought me back, like, ten copies, and I just put one on my wall and, well, that’s it, really.”

O’Mara remembers seeing the photo but doesn’t remember bringing it back to Oakley’s headquarters in Irvine, California. He agrees that he’s the only logical person who could have been the photo’s mule in 1997.

“I remember just going, ‘Damn, that’s sick.’ Those were my words,” O’Mara says. “You shake your head at how impressive he was on a motorcycle, even as a rookie.”

O’Mara reported to two people at Oakley: Louis Wellen, the director of sports marketing, and Scott Bowers, the vice president of sports marketing. “We were all, like, awing over it, looking at it in the office,” Bowers says. “I think even a little bit of the roughness added to it. It wasn’t a typical photoshoot shot where you get the perfect resolution, the perfect color.”

Nobody remembers the original 4”x6” Kodak print that O’Mara brought back. Not even Tom Moyer, the founder and creative director of M1, then Oakley’s advertising design agency, remembers the color photo. Moyer and his team created the Oakley “look” that was applied to hundreds of photos for athletes in dozens of sports, “this high-contrast, black-and-white manipulated image with the backgrounds blurred,” Moyer says. His team added motion to emphasize the athlete and movement. In the Carmichael photo, specifically, softening, darkening and blurring the crowd created an illusion he refers to as “atmospheric perspective.”

“We wanted to enhance what was already there,” he says. “It’s a very powerful image. One of the things that we really tried to do was make sure that any time anyone saw a piece from Oakley, they knew it was Oakley right away. Almost even without the logo, they knew.” After treatment, Moyer would have submitted a proof to Oakley for a first round of edits.

When Scott Taylor, an Oakley field representative, received a box of approximately 150 Ricky Carmichael posters, he was asked to quickly get them in the hands of all his dealers in Florida. In early ’98, he got another urgent memo: get the posters back.

“I think we’ve all grown to love this photo, but when I first saw it, I think my thought was, ‘Cool whip, but how did he get that angle?’” Coombs says. “That’s when it became sort of this Zapruder film of motocross. It wasn’t who got shot or who fired the gun; it was who shot the photo? When you have a floor pass for supercross, you’re usually shooting up at a guy when he’s in the air, or you’re shooting him tight in a corner.”

“[I] loved it as soon as I saw it,” Oakley’s founder, Jim Jannard, says in an email. “I made the call to use it for multiple things, including a poster. Really don’t remember much about it other than I loved the shot.” Bowers and Wellen both say that, despite being a public company by 1997, Oakley still had a “small” feel, and Jannard oversaw the major design and marketing decisions.

“I could see Jim saying, ‘Let’s run with it, and if we have to, we’ll beg for forgiveness if the photographer comes forward,’” Bowers says.

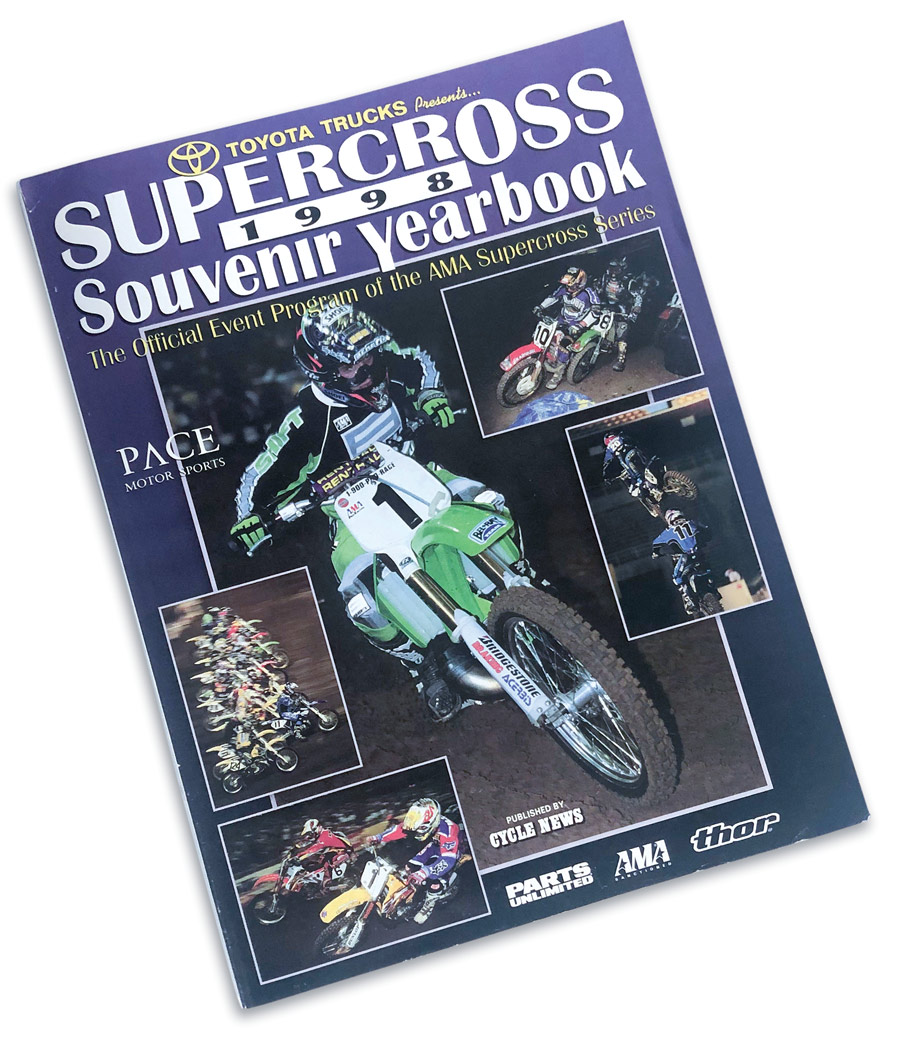

he iconic (and now very rare) Oakley poster went into production first—when exactly is unclear, but certainly at some point in the second half of 1997. The eight former Oakley employees I spoke with can’t recall exact timelines or production runs. Bowers says an average poster run started at 5,000, but this one, being segmented for motocross, could have been less. Oakley dealers received them as gifts from their field representatives. A two-page version of the photo appeared as an advertisement in the ’98 AMA Supercross program, the only small-format print version of the image.

How the image wound up on a billboard is its own story. In 1997, Oakley had space on I-405, the Los Angeles-area freeway notorious for its heavy traffic. (According to a 2012 Humboldt State University study, the entire 72 miles of 405 saw average annual daily traffic of between 245,000 and 354,000 automobiles.) Today, this specific billboard on the 405 South (near LAX) garners 1 million impressions per week, according to Outdoor Media, owners of the space. Renting the 14’x48’ placard today runs $47,200 for a four-week campaign. Oakley had the billboard locked up in a multi-month campaign, and that fall, they used it to promote a Kevlar material used in the company’s first footwear product, Shoe One. The ad, according to Bowers, featured a hypodermic needle dripping with Kevlar and “O Type Positive” as the only copy.

“We received so much hate mail,” Bowers says. “This was also somewhat at the height of the AIDS epidemic, and bad use of needles. So we immediately pulled it down, and we couldn’t think of another image to run.”

Urgently in need of a replacement, someone suggested the Carmichael photo, taken by the photographer nobody could find. What is more astonishing here: that a ticketholder’s photograph–a regular 4”x6” print, probably covered in fingerprints by the time it reached the art department–could be become a 672 sq. ft. advertisement, or that a motocross rider soared high above one of the busiest freeways in the entire world?

It certainly impressed Carmichael, who didn’t know about it. O’Mara picked him up at LAX when RC came to California for off-season training or testing. Rounding a bend on the 405, O’Mara said, “Hey, Ricky, look at that.” Carmichael, 18 at the time, could only muster a “Holy crap!” before the monster-sized version of himself whizzed out of view.

Coombs needed an image for issue number 9/volume 8 of his Racer X Illustrated newspaper, and when he heard about the Oakley billboard, he asked contributor Chris Hultner, who lived in Southern California, to get a photo of it. Hultner pulled over to the shoulder, jumped out of the car, snapped one photo across the ten lanes of traffic, and left. The issue shipped by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, back near Buffalo, David St. Onge discovered he’d been published in the February 1998 issue of Motocross Journal, a now-shuttered sister publication of Motocross Action. It was a half-page color photo of Kevin Windham at the ’97 Broome-Tioga Motocross National–a photo he took from the spectator’s side of the fence–which appeared on page 79. The editors spelled his name incorrectly, a small but cringe-worthy injustice. It was his first published photo—or so he thought. He didn’t get paid, but the editor agreed to secure him press credentials to any East Coast race. Between 1998 and 2000, St. Onge estimates he attended maybe 15 races, and always sent in his slides. He never got another photo published.

His first race as a credentialed photographer? The Arenacross in Hampton, Virginia, January 16-18, 1998.

hen St. Onge returned home from Virginia, he visited oakley.com. The entire screen filled up with a photo of Ricky Carmichael. His photo. The next morning, January 19, he called Racer X and talked to Coombs, who remembers being asked what he thought the photo was worth from Oakley.

“I can remember thinking a thousand dollars, maybe two thousand,” Coombs says. “I remember him saying, ‘It’s got to be ten thousand’ or something like that.”

St. Onge vividly recalls Coombs telling him, “I’m sure Oakley has a check for you,” and that he would contact Oakley on his behalf. In the meantime, a client of St. Onge’s recommended a lawyer; he called, and the lawyer, who dealt in song rights, assured St. Onge–provided he had negatives and a true story–it was an open-and-shut case and that he should go after Oakley. St. Onge said he wanted to give Oakley a chance to call back first.

The photographer spent three full, agonizing days reflecting, stewing. In that time, he also discovered the run of posters with Oakley’s copyright along the edge. He couldn’t get the one-hit-wonder analogy out of his head, and his angst grew.

“So now I’m getting pissed,” he explains. “I’m trying to get a career started. Man, what a way to start it with this photo, right? But nobody knows I shot it. To me, this is a big deal. Maybe [Oakley is] busy. It’s not a big deal to them. But for me, this was my whole world.”

He waited until Thursday, January 22, then called the lawyer, who told him to register the photo with the Library of Congress, which he did. An Oakley representative finally called that afternoon. St. Onge can’t remember a name, but he told the woman it was too late, that he’d decided to handle it with a lawyer. A former Oakley legal counselor declined to comment, citing attorney-client privilege, so why Oakley took three full days to call St. Onge back remains a mystery. One theory assumes they were cleaning up.

“I remember driving around my territory at 100 mph and peeling out of parking lots,” Taylor says. “Nobody was giving those things up. They became gold!” Taylor made sure the walls of his dealers were clean, but he only got back a small handful of the posters, mostly from non-moto resellers.

Meanwhile, out on the 405, Michael Jordan replaced Carmichael on the billboard.

When St. Onge dug in with his lawyer the following week, the case took a bizarre twist: his attorney wanted to go after everyone. St. Onge had visited the University of Buffalo to study copyright law and discovered willful copyright infringement punishable up to $100,000 per use. He counted four uses: the posters, the supercross program, Oakley’s website, and the billboard. But he wondered, Is each of those considered one use? Or is each poster printed considered one use? The lawyer said that was up to a judge to decide and said, “That’s why we want to sue everybody, including Ricky, Kawasaki, Pontiac Silverdome”—and, of course, Oakley. St. Onge balked and said absolutely not. “The only people that did anything wrong here was Oakley,” he told the attorney. A week later, the lawyer said he didn’t want to litigate the case, that Oakley wasn’t a big enough company. “I remember him specifically saying a company “the size of McDonald’s would be worth going out and litigating it. Let’s face it, [lawyers] are gold-diggers, right? Because he knew the more we could get off a judgement, the more they’d make.”

The big lawsuit against Oakley over a mystery photograph never actually happened. That’s an urban legend. St. Onge bristles when he hears people refer to it as “the most expensive photo in motocross history,” because it gives the illusion of a lucrative payday and a future spent on Easy Street. Instead, he settled out of court for “low five figures,” politely declining to say exactly how much. The lawyer took a third. Wellen says he knew Oakley had spent $15,000 to purchase global rights for other images used in a similar fashion. St. Onge admits that, had Oakley been able to find him before using the photo, he wouldn’t have had the guts–or the experience–to negotiate. He would have gladly taken $1,000.

otocross on a billboard in Los Angeles was (and still is) a big deal. Factor in the settlement, the legal fees, the entire ad campaign, and printing and distribution costs, and the 1997 Carmichael photo by David St. Onge is easily a six-figure image. It undoubtedly is the most expensive photo in dirt bike racing history, and one that Moyer is still particularly proud of. Of the hundreds of photos he worked on for Oakley, he says the Carmichael shot received the most feedback. “That was a very successful image,” he recalls. “That was one of the better ones. I want to thank [St. Onge] for the image, because we had a lot of fun working on it. I’m glad that it still has power and still speaks to people.”

The settlement was finished within eight weeks of that arenacross race in Virginia, and St. Onge used the money to buy a full-frame Canon EOS-3 and a variety of lenses. He continued to shoot at select races with press credentials. Pat Schutte, the public relations director for Pace Motor Sports in 1998, liked to introduce St. Onge with a punchy prelude: “This is the guy who shot the Carmichael photo.”

David St. Onge became a cult figure in the small pool of regular photographers, and Schutte recalls them all being on his side. Joe Bonnello, a particularly witty lensman, had the most succinct and honest line of all when he said, “Technically, it’s a piece of shit. Aesthetically, it’s a masterpiece.”

After failing to gain traction as a motorcycle photographer, St. Onge attended his last race in 2000 and re-focused on his recording business, which continues today. He had trepidation about telling this story, even more than two decades later.

“My fear was people would see the actual photo and be let down,” he says. He couldn’t be more wrong. Until now, the original version had never been published, and only a small handful of people had ever seen it. It’s like he opened up a time capsule—the one we all buried on the playground in fifth grade, before Carmichael was the GOAT, before energy drinks and four-strokes were things, and the world was a much bigger place because we weren’t all connected by smart phones and social media. With this image, we all get to drift back to the late 1990s. For motocross fans, it’s a mystery solved, a special treat, a tale finally told. Because today we’re inundated with so many photos that our thumbs never stop moving.

Sure, there’s a story behind every photo. But not every photo has a story.