he introduction of the Unadilla National marked the first time that 125cc motorcycles would be anything more than a GP support class—and what a year ’89 was for the tiddlers. Yamaha’s Damon Bradshaw and Honda’s Mike Kiedrowski, both first-year pros, took the championship battle down to the very last moto, on October 15, 1989. (Unadilla was still hosting the 250cc USGP in July ’89 and wanted the outdoor national to be as far away from the July date as possible.) Bradshaw ended up winning the day, but it was Kiedrowski who won the title with three points to spare.

That same day, Jeff Ward became the first rider in AMA Supercross/Pro Motocross history to win titles in all four major championships that existed back then, as he added the 500cc MX title to the 125cc MX and 250cc MX and AMA Supercross ones he already possessed. And in a bit of an ironic twist, it was French import Jean-Michel Bayle who won the 500 Class that day—the same JMB who’d lost the ’89 250cc U.S. Grand Prix at Unadilla to Rick Johnson earlier that summer.

The next year, Unadilla again hosted the last round of AMA Pro Motocross, Wardy again clinched the 500 title, and Kiedrowski was locked in another battle that would go down to the last 125 moto, only this time it was with Suzuki’s Guy Cooper, and this time he didn’t win. Cooper needed to stay right behind the leader Kiedrowski to beat him in points, and the muddy Unadilla circuit wasn’t doing him any favors—he fell twice and lost his goggles and a couple of positions. But he got a gift with two laps to go when runner-up Mike LaRocco, his Suzuki teammate, got a flat tire. Cooper overtook him and ended up winning his one and only AMA Pro Motocross title by a single point.

For three years (1989-’91), Unadilla hosted both the USGP and an outdoor national, and the added traffic began to show in the way the soil looked when riders showed up. The once-lush grass no longer came in like it used to. Ninety-two was the last year on the GP schedule for ’Dilla, and soon there would be more bikes on the track, as the Robinsons decided to finally open it to amateurs in the mid-nineties.

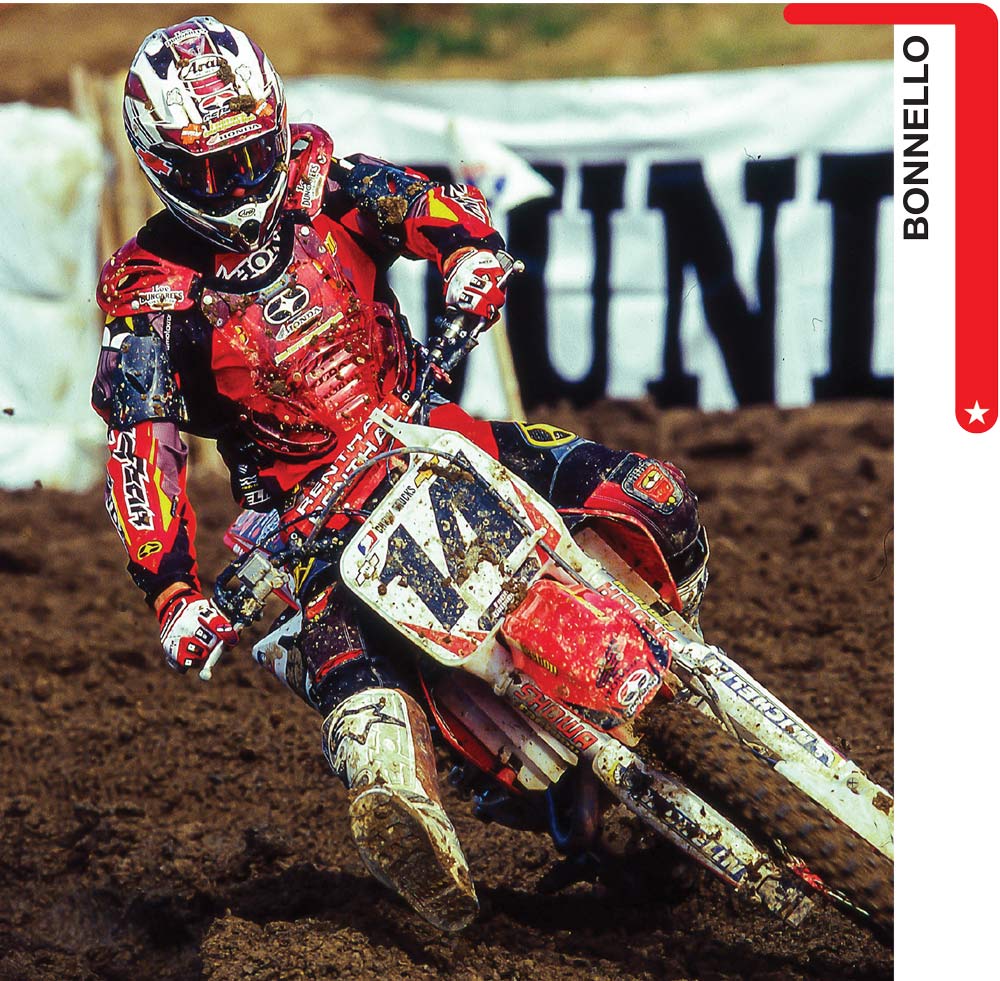

Yet Unadilla still maintained its international flavor, as Grand Prix riders often signed up to compete there if they had an off-weekend. In 1997, Stefan Everts, Pedro Tragter, and U.S. expats Mike Brown and Bob Moore all came to race the Unadilla National. Adding to that was the fact that Everts’ old nemesis, three-time world champ Greg Albertyn of South Africa, was there waiting for him as a part of Suzuki’s AMA team. Everts might have even won the 250 overall had he not collided with John Dowd and gone down at the top of Screw-U in the second moto.

“I came here because I always wanted to enter a national and see how I would do, and I think I showed that I could keep pace with the Americans on their own tracks,” said Everts, who ended up fourth overall on a production CR250 that was very different from the works Honda he was riding on the 250 Grand Prix tour.

t was at the same ’97 Unadilla National that Ricky Carmichael first competed. That was the start of a somewhat acrimonious relationship, as the rookie phenom struggled with the track and finished fourth overall in one of the worst finishes of his 125cc career. Making matters worse, his new rival Kevin Windham blitzed the field in both motos.

“I feel really good on this track, and I’ve now won here two years in a row,” Windham said after the race.

Carmichael was less enthusiastic.

“I don’t feel good about how this day went,” he told Cycle News. “I wasn’t like my normal self. I hit a stick and crashed after the Screw-U deal. It went downhill from there. All in all it was a bad day.”

“Today was unbelievable,” Windham told Cycle News. “It’s been such an unbelievable run for Ricky. It really became apparent to me when I was doing my victory lap, just exactly what he had accomplished. It’s a phenomenal thing. I crossed a big hurdle today. It’s a good feeling.”

It was the opposite for Carmichael, and the beginning of two weeks he would rather forget, as Windham would also beat him the following race at Washougal. It was during that time that Carmichael decided to make the switch to a four-stroke, as the evolution of the thumpers had sped up considerably. He won the last three rounds on his CR250—the last three nationals ever won by a 250cc two-stroke—then moved up to 450s and went on an even longer winning streak. He never lost at Unadilla again, nor did he let Windham beat him outdoors again, other than a DNF at the 2006 Glen Helen finale.

“What can I say? This track has been good to me, and I came here with optimism,” said Windham, who had not won a national since that ’03 Washougal win. “This track requires a lot of finesse, which is maybe why I always liked it here.” Windham’s three wins at Unadilla are the most he would have at any national track.

n 2010, Unadilla was televised live on NBC for the very first time. That may not seem like a big deal a decade later, but it certainly was back then.

“That was crazy,” Jill Robinson offers. “We’ve been doing this since 1969. There are times where we would find ourselves asking one another, ‘Did you ever think we would see the day?’ Like when they made motocross toys and you could find them on the shelves at Toys “R” Us and you would say, ‘Did you ever think we would see the day when they had toy dirt bikes at the mall’ or wherever. That’s what the live NBC show felt like. For us, that was a pretty big deal. We had been on TV before, but it was always tape-delayed and shown later. It was never like, ‘Three, two, one—you’re on the air!’ That first time was kind of surreal for us.” As it stands now, Unadilla’s 50th anniversary race will also be shown live on NBC.

“The whole Robinson family was always involved, but Peg was the one that really got things done,” Roger De Coster, a regular visitor to Unadilla since 1970, said upon her passing. “Ward was one everyone knew as the promoter, but if you wanted something done right away, you went to her. She was the foundation of the family. She was a great lady, always very polite, and she just did a lot of great things for motocross over the years.”

changing of the guard was at hand during that first live NBC race, as Ryan Dungey and Ryan Villopoto were emerging as the sport’s next superstars, taking the places of Carmichael, Stewart, Windham, and even Chad Reed, who would win Unadilla in 2009 en route to the Lucas Oil Pro Motocross Championship. Villopoto and Dungey started taking turns winning the 450 Class each year, first Dungey in ’10, then RV in ’11, then back to Dungey in ’12. By the time their careers were over, each of the Ryans would win four times at Unadilla. And when they moved on, they were replaced at the front of the Unadilla pack by a couple of riders who, back in the day, would have been right at home here for a U.S. Grand Prix: Germany’s Ken Roczen and France’s Marvin Musquin, who have kept Eli Tomac from winning a 450 race here so far. Each were FIM World Champions in Europe before they brought their talents to America and almost certainly would have stayed in Europe in a different era.

“It’s very similar to the problem the Augusta National golf course had when John Daly and those new guys burst onto the scene, Robinson says. “The course forever was the same, but then suddenly guys could drive the ball 400 yards. They knew they had to keep the ambience and feel and tradition of the course, but they really had to update and change it to make it fit the new generation of big-hitters and the new high-performance clubs they were using.

“Well, with today’s race bikes and the great suspension and engines and mapping and all that they have, you can’t have a flat, smooth track,” he adds. “It just doesn’t work. The ruts and berms don’t form like they used to, and if they did, it would be nothing to these guys. So when we do make a track change, we really keep that natural Unadilla feel to it, and not have it be like some supercross track in the middle of a field. That’s the challenge that all of us promoters have now.”

“Still today, even though Unadilla has changed quite a bit, I feel it’s still one of the best tracks of all,” De Coster says. “It’s very technical, it still requires good technique, and it’s not an easy track by any means.”

Emig also made some very close friendships over the years with members of the Unadilla faithful, and that added to his love of the place. He plans to be there on August 10 when it celebrates 50 years as an American motocross classic.

“I really look forward to getting back there and seeing what’s become of the track,” he says, “though no matter what little changes they make, it’s still going to be rough and choppy and the same man’s track it’s always been.”

“You have to race Unadilla incredibly differently, because she will bite you—she will put you right on the ground,” says Jill Robinson—which prompts a follow-up question: Is Unadilla actually a girl? “I think it’s a she,” Jill laughs. “I say that because she has a temper.”

People have long said that racing can be a cruel mistress. Well, now we know that Unadilla can apparently be one, too, and we look forward to being very careful around her for another 50 years.