PHOTOS: DAVID DEWHURST

PHOTOS: DAVID DEWHURST

PHOTOS: DAVID DEWHURST

BROC GLOVER (YAMAHA): Nineteen eighty-five—that was the year David Bailey had a kangaroo-skin-covered seat! I mean, what is the point of having a kangaroo-skin seat? What was the performance advantage? Was it Honda saying, “We have money and we have to spend it?”

BROC GLOVER (YAMAHA): Nineteen eighty-five—that was the year David Bailey had a kangaroo-skin-covered seat! I mean, what is the point of having a kangaroo-skin seat? What was the performance advantage? Was it Honda saying, “We have money and we have to spend it?”

DAVID BAILEY (HONDA): Broc was really funny in his comments—and he had a lot of comments. He would have comments riding behind me in a race.

JOHNNY O’MARA (HONDA): I was just a kid winning in the Indian Dunes area, which was up north just a little bit above L.A., and I happened to be affiliated with Al Baker, and that got me a Mugen Honda ride, which put me on the map.

JEFF WARD (KAWASAKI): I had won the ’84 125cc National Championship, and I was sitting pretty good. My contract was up, and I was definitely happy with Kawasaki and where the bikes were going.

BOB HANNAH (HONDA): As far as the ’85 Honda, I really don’t know if it was all that much better than an ’83, in my mind. The ’83 bike would have been very, very hard to beat once we got it tuned in.

GLOVER: Kawasaki had a shock dyno, and [team manager] Roy Turner was spending a huge amount of time on it. I remember feeling how slow the Kawasaki dampening was. It was just so stiff that it just seemed odd to me, but looking back on it, those Kawasaki guys were already on what truly worked.

GLOVER: I remember Gary Bailey riding my practice bike and saying, “Hey, is your race bike even close to this bike?” I said, “Yeah, it’s actually almost identical.” And he said, “Identical to this? This thing is so far off it’s not even in the same area code compared to David’s bike.”

WARD: I never rode a Honda. I never wanted to. Yeah, I could have probably ridden somebody’s bike at some time, but I never did. I didn’t ride a Honda just because I didn’t want to like it more than mine. I knew my bike was as good as theirs, and I also knew that I wanted to stay with Kawasaki.

RON LECHIEN

BROC GLOVER (YAMAHA): Nineteen eighty-five—that was the year David Bailey had a kangaroo-skin-covered seat! I mean, what is the point of having a kangaroo-skin seat? What was the performance advantage? Was it Honda saying, “We have money and we have to spend it?”

BROC GLOVER (YAMAHA): Nineteen eighty-five—that was the year David Bailey had a kangaroo-skin-covered seat! I mean, what is the point of having a kangaroo-skin seat? What was the performance advantage? Was it Honda saying, “We have money and we have to spend it?”

DAVID BAILEY (HONDA): Broc was really funny in his comments—and he had a lot of comments. He would have comments riding behind me in a race.

JOHNNY O’MARA (HONDA): I was just a kid winning in the Indian Dunes area, which was up north just a little bit above L.A., and I happened to be affiliated with Al Baker, and that got me a Mugen Honda ride, which put me on the map.

JEFF WARD (KAWASAKI): I had won the ’84 125cc National Championship, and I was sitting pretty good. My contract was up, and I was definitely happy with Kawasaki and where the bikes were going.

BOB HANNAH (HONDA): As far as the ’85 Honda, I really don’t know if it was all that much better than an ’83, in my mind. The ’83 bike would have been very, very hard to beat once we got it tuned in.

GLOVER: Kawasaki had a shock dyno, and [team manager] Roy Turner was spending a huge amount of time on it. I remember feeling how slow the Kawasaki dampening was. It was just so stiff that it just seemed odd to me, but looking back on it, those Kawasaki guys were already on what truly worked.

GLOVER: I remember Gary Bailey riding my practice bike and saying, “Hey, is your race bike even close to this bike?” I said, “Yeah, it’s actually almost identical.” And he said, “Identical to this? This thing is so far off it’s not even in the same area code compared to David’s bike.”

WARD: I never rode a Honda. I never wanted to. Yeah, I could have probably ridden somebody’s bike at some time, but I never did. I didn’t ride a Honda just because I didn’t want to like it more than mine. I knew my bike was as good as theirs, and I also knew that I wanted to stay with Kawasaki.

BROC GLOVER (YAMAHA): Nineteen eighty-five—that was the year David Bailey had a kangaroo-skin-covered seat! I mean, what is the point of having a kangaroo-skin seat? What was the performance advantage? Was it Honda saying, “We have money and we have to spend it?”

BROC GLOVER (YAMAHA): Nineteen eighty-five—that was the year David Bailey had a kangaroo-skin-covered seat! I mean, what is the point of having a kangaroo-skin seat? What was the performance advantage? Was it Honda saying, “We have money and we have to spend it?”

DAVID BAILEY (HONDA): Broc was really funny in his comments—and he had a lot of comments. He would have comments riding behind me in a race.

JOHNNY O’MARA (HONDA): I was just a kid winning in the Indian Dunes area, which was up north just a little bit above L.A., and I happened to be affiliated with Al Baker, and that got me a Mugen Honda ride, which put me on the map.

JEFF WARD (KAWASAKI): I had won the ’84 125cc National Championship, and I was sitting pretty good. My contract was up, and I was definitely happy with Kawasaki and where the bikes were going.

BOB HANNAH (HONDA): As far as the ’85 Honda, I really don’t know if it was all that much better than an ’83, in my mind. The ’83 bike would have been very, very hard to beat once we got it tuned in.

GLOVER: Kawasaki had a shock dyno, and [team manager] Roy Turner was spending a huge amount of time on it. I remember feeling how slow the Kawasaki dampening was. It was just so stiff that it just seemed odd to me, but looking back on it, those Kawasaki guys were already on what truly worked.

GLOVER: I remember Gary Bailey riding my practice bike and saying, “Hey, is your race bike even close to this bike?” I said, “Yeah, it’s actually almost identical.” And he said, “Identical to this? This thing is so far off it’s not even in the same area code compared to David’s bike.”

WARD: I never rode a Honda. I never wanted to. Yeah, I could have probably ridden somebody’s bike at some time, but I never did. I didn’t ride a Honda just because I didn’t want to like it more than mine. I knew my bike was as good as theirs, and I also knew that I wanted to stay with Kawasaki.

RON LECHIEN

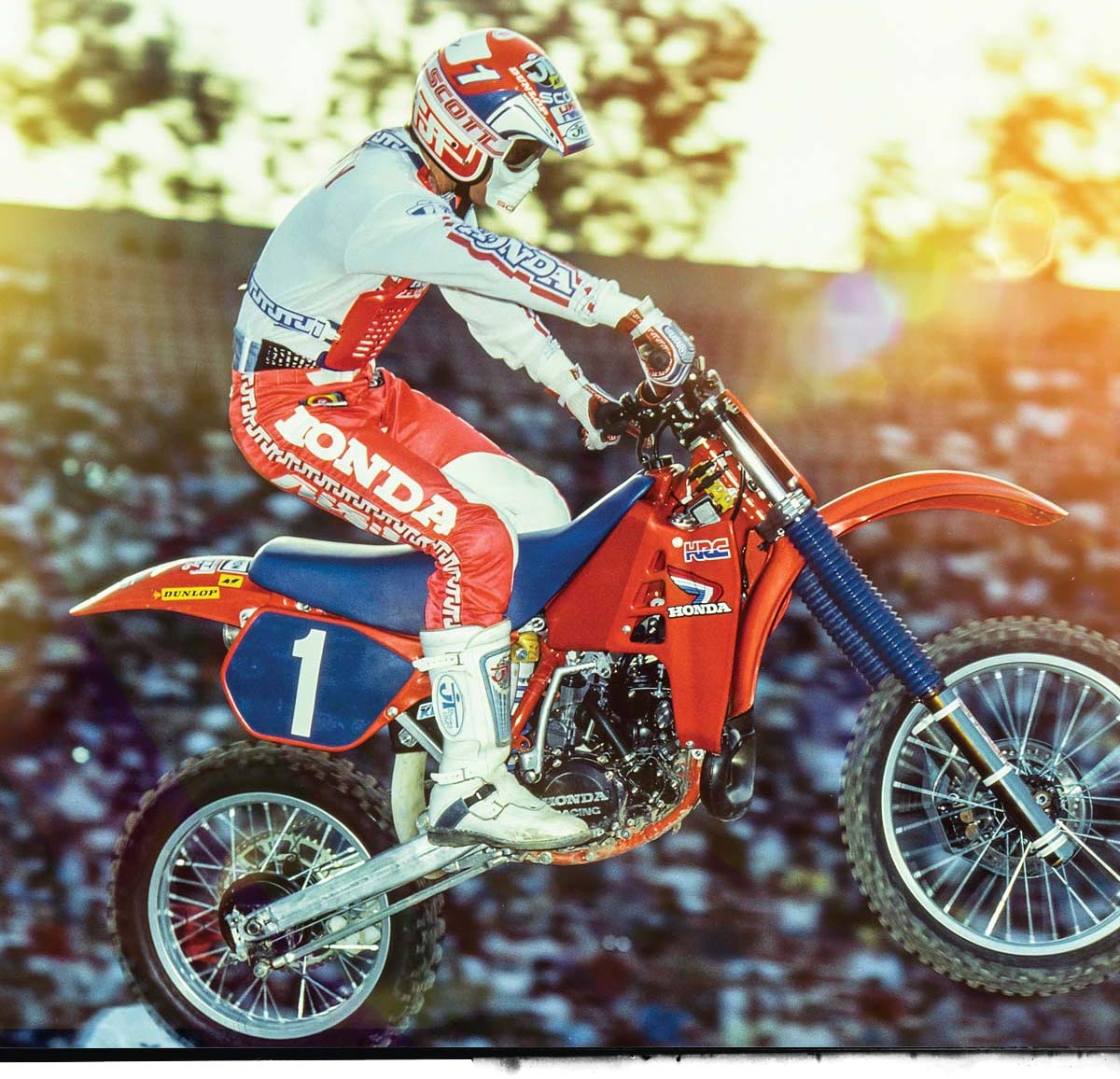

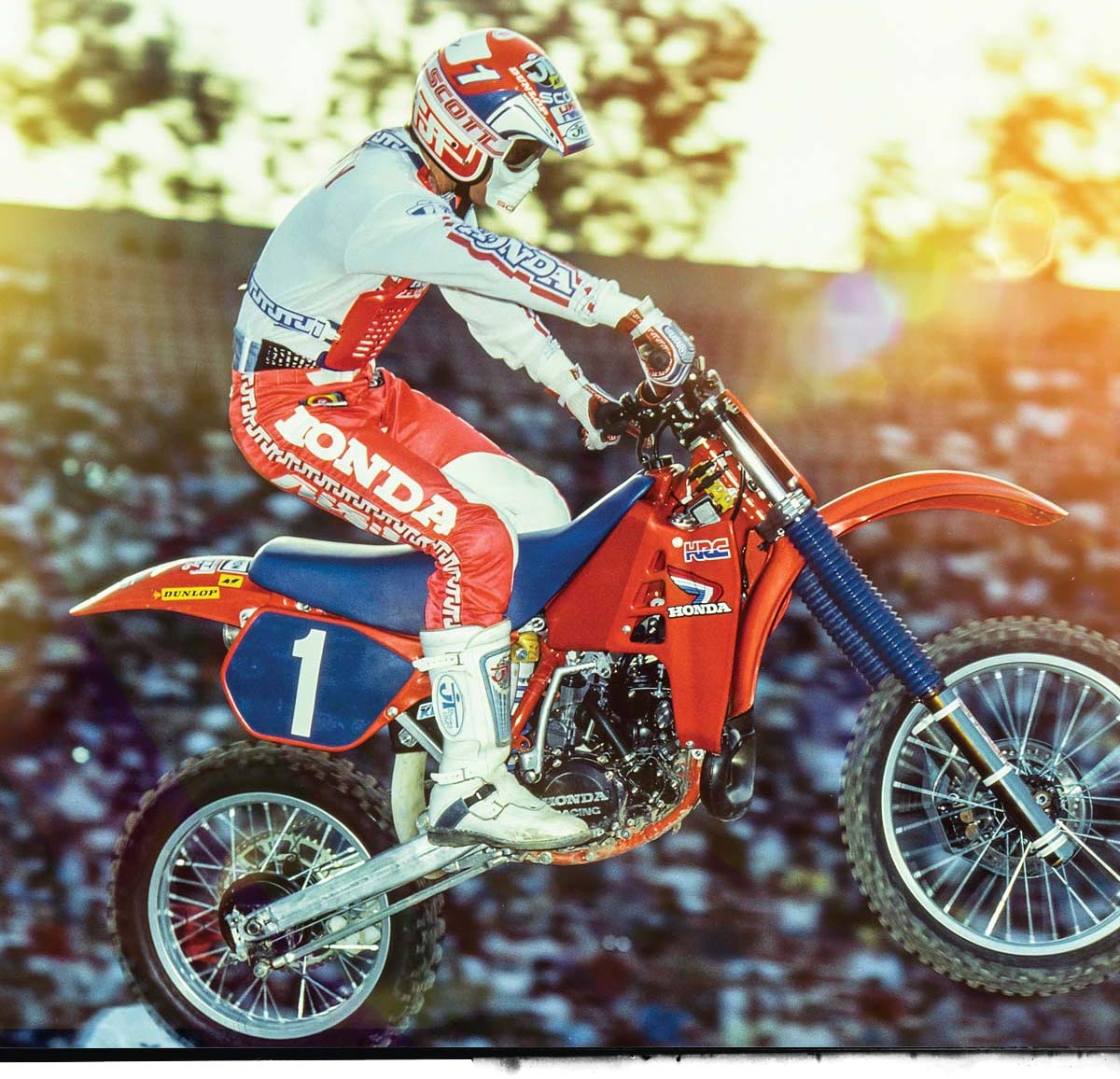

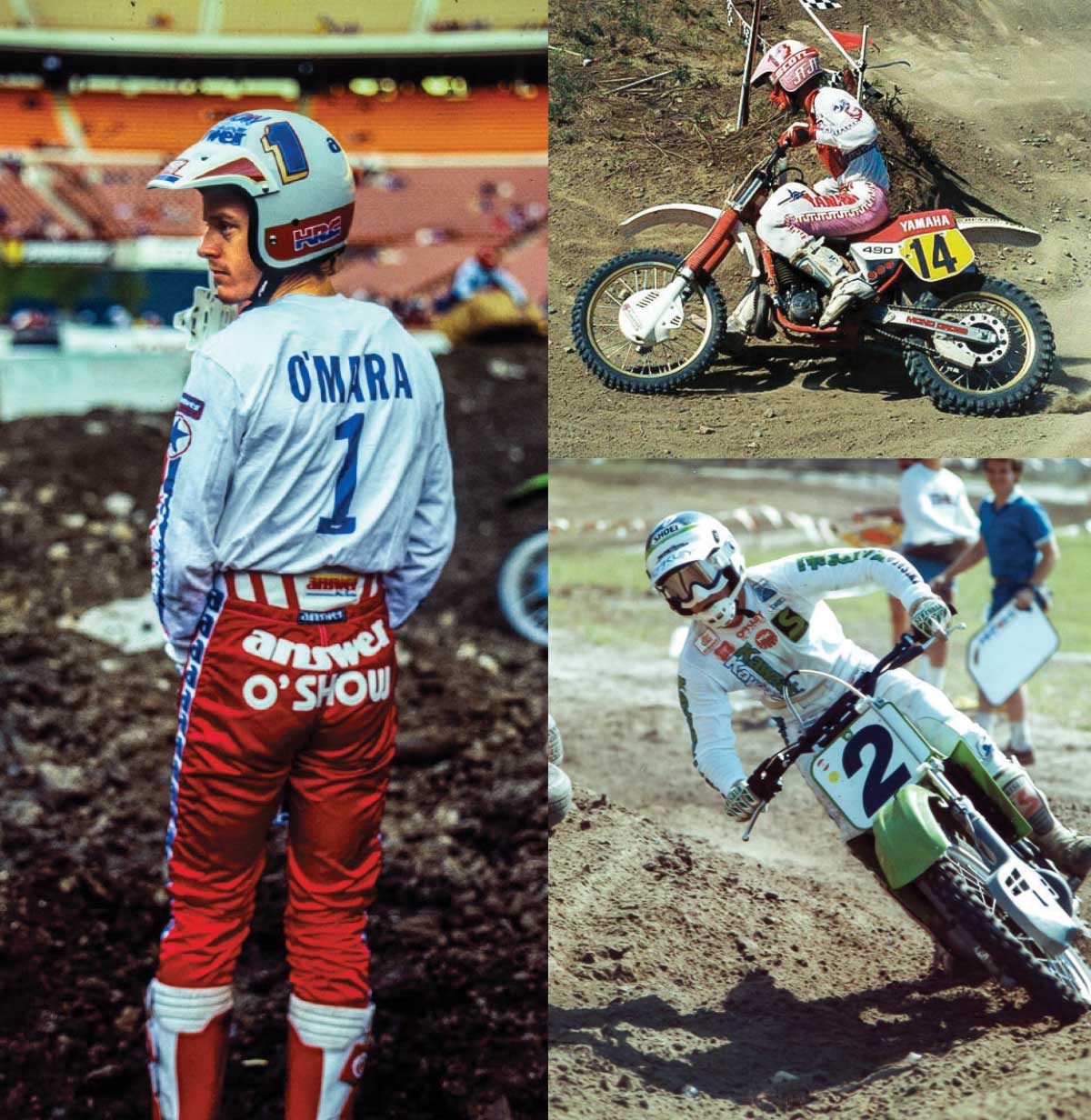

Johnny O’Mara (1) used his works Honda RC250 to win the ’84 AMA Supercross Championship, while Jeff Ward (2) used his works Kawasaki SR250 to take both the ’85 AMA Supercross and 250 Pro Motocross titles. And somehow Broc Glover (14, shown here at the USGP) and his already-outdated, air-cooled Yamaha YZ490 topped David Bailey for the ’85 500cc title.

Johnny O’Mara (1) used his works Honda RC250 to win the ’84 AMA Supercross Championship, while Jeff Ward (2) used his works Kawasaki SR250 to take both the ’85 AMA Supercross and 250 Pro Motocross titles. And somehow Broc Glover (14, shown here at the USGP) and his already-outdated, air-cooled Yamaha YZ490 topped David Bailey for the ’85 500cc title.

RON LECHIEN (HONDA): I was all right with riding the 125 in 1985. Knowing the ’85 Honda works 125 was going to be such a great bike, Honda wanted me down there on that bike, and they asked me to do it. I was like, “No problem!”

RICK JOHNSON (YAMAHA): I think the most works thing Yamaha gave us that year was a works disc front brake—everything else was absolute production. Both Broc and I struggled, but the good thing about it was that Broc and I had production bikes to practice on. We rode the bikes really well. I rode the 250 well, and Broc rode the 500 well, and that thing was the biggest pile of shit ever.

GLOVER: It was at Mount Morris where I finally bunkered down and said to [Yamaha mechanic] John Rosenthal, “Hey, until we fix this part of our bike, we’re going to struggle. Let’s just do one thing only: let’s work on the bottom of the bike.” The bike would bottom out like crazy. It would beat the snot out of me. I said to John, “Let’s just fix that first and foremost before anything else.” Believe it or not, we spent an entire day riding through one dip. Eventually, finally, we figured out the way to fix it was by adding a ton of low-speed dampening, just like Kawasaki. It was all low-speed stuff. If that wouldn’t have happened, there was no way I would have won that championship.

GLOVER: People still kind of recognize the fact that I was loyal to Yamaha for so long [1977-’88]. I look back at it, and it wasn’t the best thing that I could have done for my career by any means. I think the part that bothers me the most, to this day, is just that people thought I had this chip on my shoulder, like, “Oh, Broc was kind of hard to please and hard to work with in some ways.” No, I wasn’t. I was there to win. I assumed that everybody was willing to put in the same effort, but they weren’t. And it showed.

WARD: One thing I remember was Broc racing the air-cooled 490 against David Bailey in the 500 class. Broc could not have had it in his brain that his bike was equal. That was the only bike you could possibly be on and not be able to convince yourself that your bike was better than that Bailey 500.

HANNAH: The ’85 was a good bike, but I think we had some power issues that we weren’t getting along with. Maybe it worked for Bailey, but not for me. I remember one time I had my bike too pipey, and I took a hammer and started smashing the head pipe at the Texas Supercross, just to tame it down where I wanted it and to keep it where I could hook it up and control it. I remember the people at Honda thinking, What the hell is he doing? I was a pipe builder. I knew how to tune the pipe!

WARD: My whole career, I never felt like I was the best supercross rider. I felt like I was the best outdoor rider—I could get that into my brain. In supercross, I just never wrapped myself around it.

O’MARA: I wasn’t surprised Jeff was that good in ’85. I always felt that our bikes had a little bit of an advantage over Wardy’s machinery, but they were working hard, too, no doubt. I know what my mindset was then as a champion, and we all thought that we were better than everybody. Nobody conceded anything.

JOHNSON: In 1985 I had the sophomore jinx. I think once you win a title—at least I know I did—you feel a little bit entitled. I didn’t work as hard. I felt like, “Well, you’re all going to respect me now.” Then I realized that they didn’t give a shit about that and they’d take you out anyway.

The one race that I’m probably the proudest of was the Vegas race, because it was 107 degrees. In the race, Wardy passed me, and when he did, he kind of stuffed me. A lap and a half later they gave the “15 minutes to go” signal and I caught him, and I knocked him off the track and I just kept going. We went back and forth, and I about died. Afterwards, I lost all this weight and started seeing stars. That kind of race didn’t matter what you were on, you were in total misery the whole time. There was no shade in sight. It was tough racing against those guys, but that’s the beauty of motocross. The individual makes a difference in moto.

The AMA’s Production Rule, which mandated that all supercross and motocross race bikes be based on production models, effectively ended the works-bike era in the U.S. It was set in motion at the end of 1984 for implementation at the beginning of 1986. Almost immediately, it was one of the most controversial moves the American Motorcyclist Association ever made. However, it also became one of the true foundational pillars of SX/MX racing in America, according to Roy Janson, an AMA official back then, and now managing director of Lucas Oil Pro Motocross.

The AMA’s Production Rule, which mandated that all supercross and motocross race bikes be based on production models, effectively ended the works-bike era in the U.S. It was set in motion at the end of 1984 for implementation at the beginning of 1986. Almost immediately, it was one of the most controversial moves the American Motorcyclist Association ever made. However, it also became one of the true foundational pillars of SX/MX racing in America, according to Roy Janson, an AMA official back then, and now managing director of Lucas Oil Pro Motocross.

y the early eighties, the concept of the works bike had gotten out of hand, in that the extraordinary costs to the manufacturers was exceeding any return on investment—that was the biggest challenge facing the industry back then. The ego-driven arms race between the Japanese factories in regard to works equipment was exceeding its benefit to the development of new products.

The whole works thing, and the effort to try to control it—which had come primarily through claiming rules—had been a horrible debacle at road racing, flat track, and motocross. We were trying to somehow balance the playing field: you could put a ton of money into one bike, but a competitor or a privateer could come claim it. But that never worked the way it was supposed to work. No one wanted to give away a $300,000 bike for $3,500, but that’s where we were for a time. And we were on the verge of losing our way.

The idea of a production rule came down from the AMA’s board. They basically said, “You’ve got to get this reined in again, and you need to tie what’s being raced back into the marketplace.”

The production rule has always been controversial, and there’s always been a cadre of passionate fans and gearheads who bemoan the loss of works equipment, but it’s never been seriously challenged. Whether we were lucky or smart, the production rule turned out to be one of the most strategically correct decisions in the history of motorsports. It’s been critical to the continued participation of all of the manufacturers.

History says we got it right ![]()

LECHIEN: Winning the 125 title was the biggest thing that ever happened to me. To win a title was a goal I set for myself when I was younger. I grew up watching Broc Glover and Marty Smith and Bob Hannah racing 125s, and that was a goal that I set for myself, and that was to be a 125cc National Champion.

HANNAH: Unfortunately, the production rule hit me really bad. I was quitting, so I didn’t really care! Then Suzuki got that news and they wanted somebody to test their production bikes, so they hired me to do that, which was a real pain in the ass, frankly. I shouldn’t have agreed to do it. They offered me an agreement for three years, and I signed on to do it. Their bike was horrid at the time, and it took years to get them to work.

BOB HANNAH

BOB HANNAH

WARD: The production rule threw another curve at us because Kawasaki did not have the best production bike. Honda probably did. If they would have said in ’86 that I couldn’t win on any other bike, I might have believed it. I mean, when I raced the 125 nationals [1979-’84], I was the only Kawasaki on the line. Nobody else rode one.

JOHNSON: I’ll never forget when I went up to Hondaland [in 1986] and I had my production Honda that I had been riding and I look over and see Johnny and David’s brand-new bikes there. Then they pull my brand-new bike out and I’m like, “I get a brand-new bike?” They said yeah and I said, “Holy shit!” Then I looked around my bike and there were three pipes and two or three cylinders and there were a couple shocks and another set of triple clamps. I said, “Holy cow, this is awesome!” Honda had a way of making you feel special as a rider.

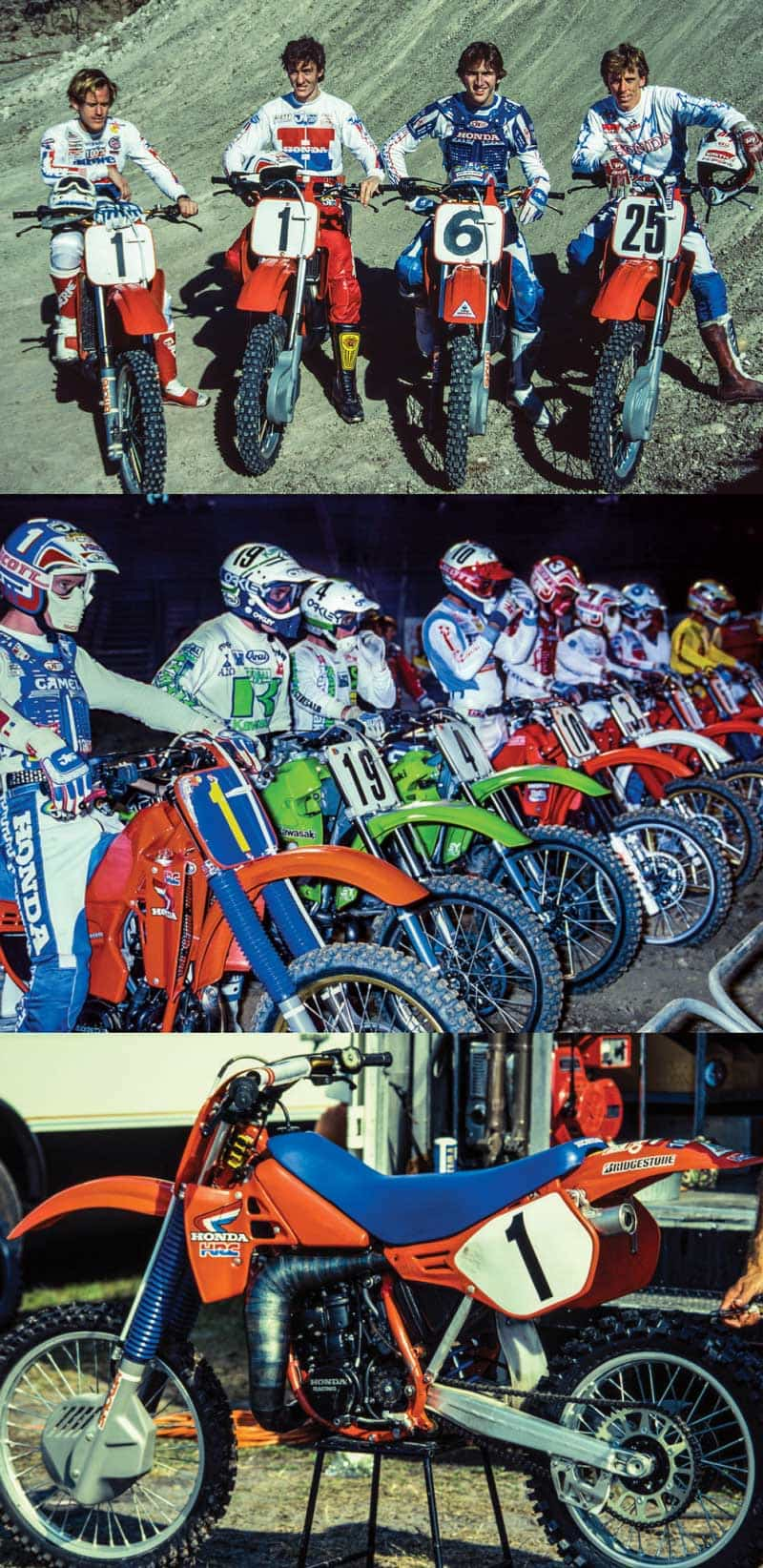

The Honda juggernaut of 1985 included (from left, above) Johnny O’Mara, David Bailey, Ron Lechien, and Bob Hannah. Despite having the works equipment, they all failed to win the ’85 SX title, which was won by Kawasaki’s Ward. (Below) Bailey’s opinion of the AMA’s production rule remains the same after 35 years: “I hated it.”

The Honda juggernaut of 1985 included (from left, second to the top) Johnny O’Mara, David Bailey, Ron Lechien, and Bob Hannah. Despite having the works equipment, they all failed to win the ’85 SX title, which was won by Kawasaki’s Ward. (Below) Bailey’s opinion of the AMA’s production rule remains the same after 35 years: “I hated it.”

HANNAH: I was really good friends with the president of Honda and with Roger [De Coster] and [Dave] Arnold. Things were really good there. I should have signed again and said, “I’ll take less money, but I want support until I’m sick of it.” If I had to do it over again, I would have said, “Honda, you don’t have to pay anything, just give me full support with a truck, bikes, mechanics, and bonuses.”

BAILEY: At the end of the year, we did the All-Japan GP in Sugo, then we went to go do some testing of the new production bikes. After we were done, I knew we had a little time while we were loading up, so I jumped back on that ’85 250 and rode and rode until Dave Arnold came down and said, “Okay, we gotta go.” I actually ignored him the first time I came around because I wanted to ride it a little bit longer. I knew that was going to be it, that this was the last factory bike I would ever ride. I knew I’d never see that bike again. And I loved that bike. It was really hard to get off it and say goodbye. I hated the production rule. Hated it. When works bikes were gone, a part of me was gone too.