of

the

Tuners

WORDS: STEVE MATTHES

of

the

Tuners

of

the

Tuners

WORDS: STEVE MATTHES

ob’s one of those guys that was there damn near when I showed up on a minibike,” Damon Bradshaw recalls. “I started with Yamaha when I was, like, eight years old. He was one of those guys that was there and you walk by the pits to this day and he’s still there.

“Yamaha is the only team I feel that’s that way,” the Beast from the East adds. “There are so many guys that are still there from when I raced 80s.”

A long time ago in motocross there was the rider and the mechanic, and that was about it. Mechanics drove with the bike in a box van and were solely responsible for its maintenance and modifications. He was also a part-time psychiatrist, nutritionist, trainer, and life coach for his rider. That all changed in 1992 when Kawasaki brought the first semi truck into the pits. The intimate rider-mechanic relationship evolved from there, incorporating a suspension guy and a motor guy as well. Then four-strokes came in with EFI, and now there’s a data guy. The mechanic became more and more of a parts-changer and less and less connected with the riders. Bob Oliver has worked through all of it.

“When I first started, every rider and mechanic were really close,” explains Oliver, whose retirement was a mutual decision between him and the company. “You and the rider definitely spent a lot more time together than you do now, and it was more one-on-one. Now you’ve got this big list of people that, when a rider comes off the track, he’s got to communicate with each one of them, as well as his mechanic. Sometimes I think it’s maybe a little overpowering to the guy in the middle. I don’t think that mechanic-rider, one-on-one closeness is what it used to be.

“When I started out with RJ [Rick Johnson], it was quite normal for the motorcycle to come back from an event, and even the rider, with tire marks on his boots, on the back of the bike, on the swingarm,” Oliver recalls. “They were riding close and touching. Nowadays if you get those kind of marks it seems like there’s going to be some kind of action and a giant confrontation is going to ensue because they even touched!”

Yamaha had a powerhouse team for many of the years that Oliver served as either a mechanic or, later on, a motor guy, but it all started when the native of Long Beach, California, took an interest in motorcycles. That led to a job with FMF in the halcyon days of Uncle Donnie Emler grinding cylinders in a makeshift race garage. Oliver then moved to DG Racing, another SoCal hop-up company. This move led to a friend named Cliff Lett who worked at Yamaha calling him to let him know about an opening with the off-road team. Oliver took the gig, working alongside another longtime industry guy, Ron Heben.

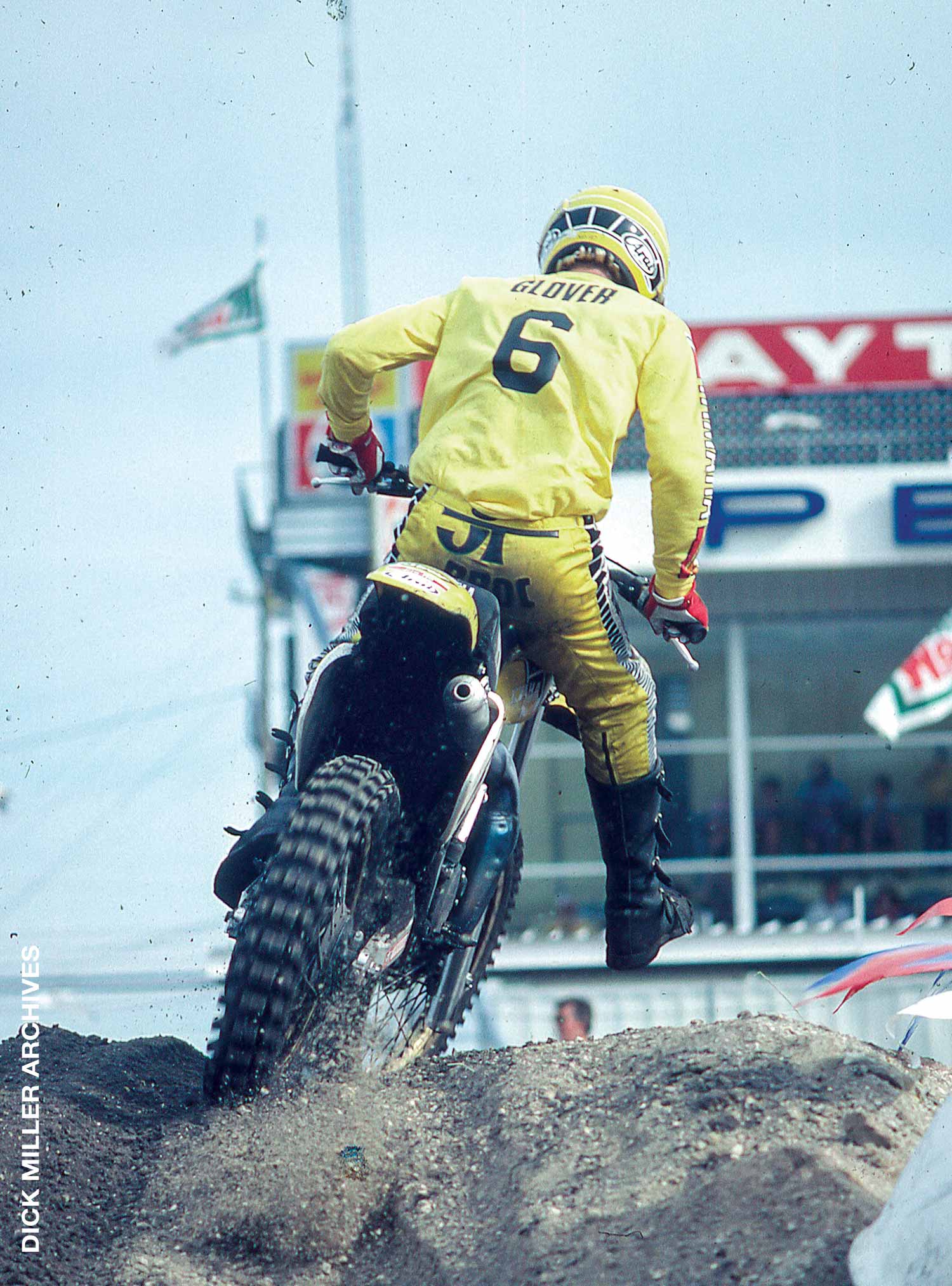

Oliver then moved to Yamaha’s in-house motor department. Besides working for Scott Burnworth in 1986, he spent his time in the motor department tweaking two-strokes (and later four-strokes) to get the maximum performance out of each racing engine. As a result, the list of top riders he’s worked with over the years is astounding: Rick Johnson, Broc Glover, Damon Bradshaw, Jeff Emig, Doug Henry, Jeremy McGrath, David Vuillemin, Tim Ferry, Chad Reed, James Stewart, Cooper Webb, Justin Barcia, and more.

hen asked what might carry over from great rider to great rider through the generations, Bob offers this: “It’s hard to meet somebody that hates to lose like they do. It’s like a personal deal for them. It’s the one thing that you could be sure: RJ, when he started moving up, when he got beat, he didn’t like it, so he just worked harder and harder. You could see that in his career, how when he was on top, he was an animal. He would just turn that way by the fact that he did not want to lose, and he didn’t take it well.

“We won a lot, and Bob was a huge part of that,” McGrath himself adds. “He was never down on me, never complained, and always tried to get the bike right. The industry is going to miss him for sure. The bikes have changed a lot, but he never did. He’s one of the unsung heroes and was a big part of those championships that I got when I was on Yamaha.”

Oliver was also front and center for motocross history when Doug Henry rode the works YZM400 four-stroke that started a revolution in the sport.

“No. Not a clue. Not really!” Oliver laughs when asked if he knew that 400 would trigger such immense change. Luckily, he’d learned four-strokes in the mid-seventies before the FMF and DG days when he worked with drag racing legend Terry Vance (of Vance & Hines fame) at a shop owned by Russ Collins.

“It had some rough edges,” he says of that first white Yamaha thumper. “You could see there was something. It was kind of like the lump of coal that’s going to turn into a diamond. You knew it’s going to happen, but it pretty much still looks like a lump of coal in the beginning.”

“That was an amazing night,” Oliver says. “There was so much work put into that bike. It was amazing. We spent a lot of time with it—and a lot of that time was carburetor related. Just to get the thing to run the same all the time was a major feat.”

iver has had a hand in a lot of Yamaha’s special projects over the years. One he remembers fondly was the made-for-TV ABC Superbikers, which combined road racing, motocross, and dirt track on special-made motocross bikes.

Beating the works Hondas and all the other OEMs is something that a company man like Oliver is driven to do. It’s not always like that now, with people switching teams much more readily, but Oliver, like Cliff White at Honda and Rick Asch at Kawasaki, bled the color of the brand he worked for, even as it changed from yellow to white to blue.

Oliver says he’ll still come out to the odd race in his retirement. He’s got a 13-year-old daughter to look after, though, and he says he’ll spend a lot of time with his wife. Oh, and ride his bicycle more—something he’s always enjoyed, at least when he could find the time. He leaves with a reputation as a racer’s ultimate wrench.

Oliver is one of the last of his breed in the sport. When asked for some final words on his career, he of course didn’t take the moment as a time to brag; he’s never been that guy and isn’t going to start now. What he did offer was typical of this highly respected master mechanic: “Once in a while I get to sit on the back porch with the dog and a cigar and a can of beer and think about, ‘You know what? That’s been pretty amazing.’”

Yes, it has. Happy trails, Bob Oliver.