PHOTOS: RICH SHEPHERD & JEFF KARDAS

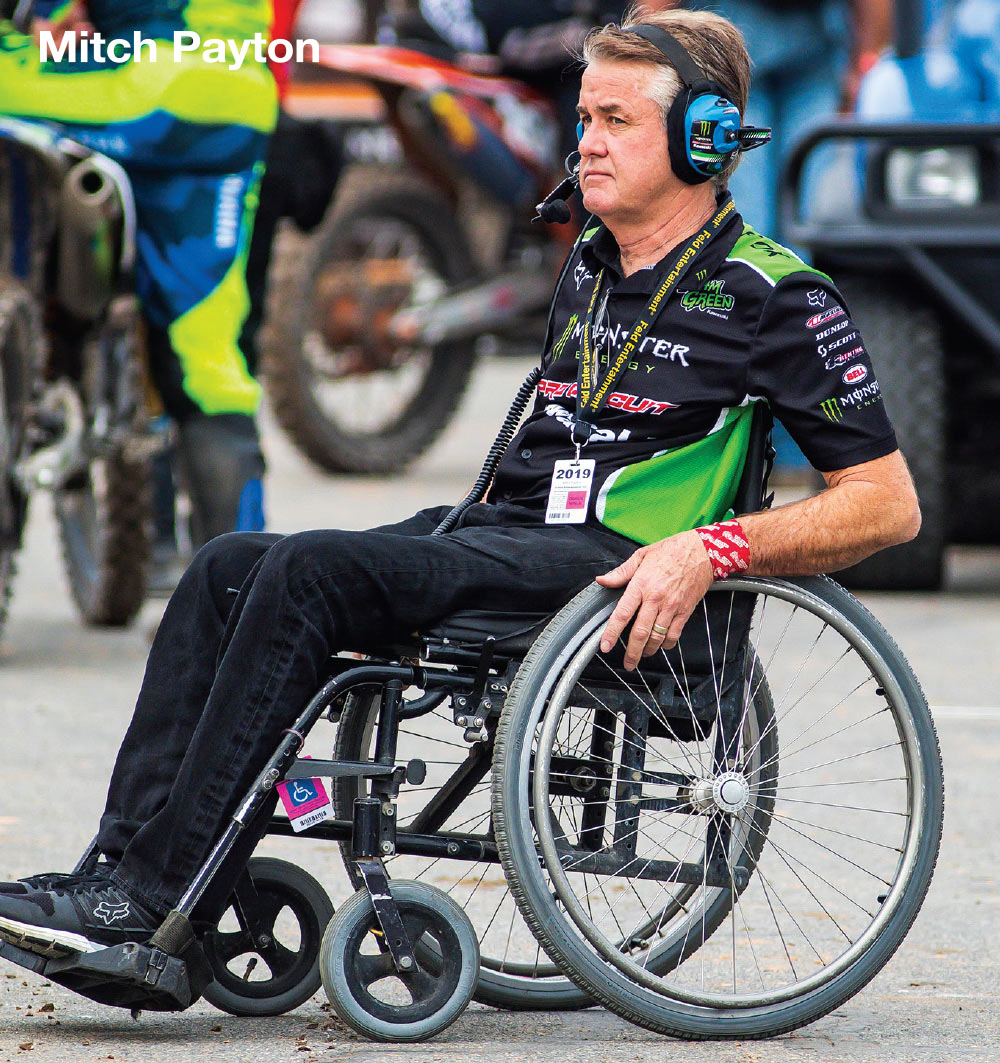

As far as brand names in this sport go, few ring with the power of Pro Circuit, the company that best married aftermarket performance with professional racing success. Yet, when you say “Pro Circuit,” everyone really thinks “Mitch”—as in company founder Mitch Payton.

Everyone knows Mitch. Everyone has a Mitch story (for a decade, we even made “Favorite Mitch Payton story?” a 2 Tribes question). This is a competitive world, but there’s too much respect for Mitch for anyone to be disrespectful. So when the tide turned and Pro Circuit finally stopped winning, it wasn’t Mitch’s engine building or business sense that got him back on top.

It took some help from his friends. And when you have more friends than anyone else, that’s a lot of help.

PHOTOS: RICH SHEPHERD & JEFF KARDAS

As far as brand names in this sport go, few ring with the power of Pro Circuit, the company that best married aftermarket performance with professional racing success. Yet, when you say “Pro Circuit,” everyone really thinks “Mitch”—as in company founder Mitch Payton.

Everyone knows Mitch. Everyone has a Mitch story (for a decade, we even made “Favorite Mitch Payton story?” a 2 Tribes question). This is a competitive world, but there’s too much respect for Mitch for anyone to be disrespectful. So when the tide turned and Pro Circuit finally stopped winning, it wasn’t Mitch’s engine building or business sense that got him back on top.

It took some help from his friends. And when you have more friends than anyone else, that’s a lot of help.

After years of coming up short in his quest to win a 250SX championship, Monster Energy/Pro Circuit Kawasaki’s Adam Cianciarulo and his mechanic, Brandon Zimmerman (left)—as well as riding coach Nick Wey—have found themselves on the verge of taking this year’s 250SX West Region crown.

Yet there he was in Seattle, pitching in for his buddy. Next to him in the team semi were current racers Adam Cianciarulo and Garrett Marchbanks, as well as former team riders Ivan Tedesco (2004–’05) and Nick Wey (1998–2000). Tedesco coaches Marchbanks and tests for the team, while Wey works with Cianciarulo. Watching those two break down video footage alongside Bones gives the Pro Circuit truck a familiar feel. This could be 2019, 2009, or 1999—well, probably not ’99, as Marchbanks was actually born in 2001!

Pro Circuit’s 250SX East Region tandem has roots, too, with Austin Forkner working with Robbie Reynard, who never rode for Mitch’s team but has run plenty of Pro Circuit parts through the years. Forkner’s teammate Martin Davalos trains at the GOAT Farm, owned by Ricky Carmichael, who rode for Payton from 1997 through ’99.

On the surface, there isn’t a real secret to this year’s success. Forkner and Cianciarulo came through Kawasaki’s amateur system with talent and came into the year healthy and ready. It’s the same way Kawasaki and Payton have always done it. It’s just more complicated than it used to be.

Kawasaki kept its 450 factory team running strong through the recession, but its amateur effort suffered. Neither Eli Tomac nor Joey Savatgy, today’s 450 riders, graduated from the amateur ranks with Team Green, nor did any other of the Kawi factory team’s recent riders, like Josh Grant, Wil Hahn, or Davi Millsaps. Savatgy is actually the first Pro Circuit grad on a Kawasaki factory 450 in a while. It’s a big change from watching Carmichael, James Stewart, and Ryan Villopoto “let the good times roll” from KX80s all the way through to the premier pro classes.

“We were very, very fortunate that Eli was available,” Stjernstrom says of signing Tomac before the 2016 season. “You’d be taking a big risk to just hope that a rider of his caliber was available.”

Now there’s a chance Cianciarulo could be racing a KX450 for the factory team in 2020. Twelve years after the recession, the rebuild is nearly complete.

After years of coming up short in his quest to win a 250SX championship, Monster Energy/Pro Circuit Kawasaki’s Adam Cianciarulo and his mechanic, Brandon Zimmerman (left)—as well as riding coach Nick Wey—have found themselves on the verge of taking this year’s 250SX West Region crown.

Yet there he was in Seattle, pitching in for his buddy. Next to him in the team semi were current racers Adam Cianciarulo and Garrett Marchbanks, as well as former team riders Ivan Tedesco (2004–’05) and Nick Wey (1998–2000). Tedesco coaches Marchbanks and tests for the team, while Wey works with Cianciarulo. Watching those two break down video footage alongside Bones gives the Pro Circuit truck a familiar feel. This could be 2019, 2009, or 1999—well, probably not ’99, as Marchbanks was actually born in 2001!

Pro Circuit’s 250SX East Region tandem has roots, too, with Austin Forkner working with Robbie Reynard, who never rode for Mitch’s team but has run plenty of Pro Circuit parts through the years. Forkner’s teammate Martin Davalos trains at the GOAT Farm, owned by Ricky Carmichael, who rode for Payton from 1997 through ’99.

On the surface, there isn’t a real secret to this year’s success. Forkner and Cianciarulo came through Kawasaki’s amateur system with talent and came into the year healthy and ready. It’s the same way Kawasaki and Payton have always done it. It’s just more complicated than it used to be.

Kawasaki kept its 450 factory team running strong through the recession, but its amateur effort suffered. Neither Eli Tomac nor Joey Savatgy, today’s 450 riders, graduated from the amateur ranks with Team Green, nor did any other of the Kawi factory team’s recent riders, like Josh Grant, Wil Hahn, or Davi Millsaps. Savatgy is actually the first Pro Circuit grad on a Kawasaki factory 450 in a while. It’s a big change from watching Carmichael, James Stewart, and Ryan Villopoto “let the good times roll” from KX80s all the way through to the premier pro classes.

“We were very, very fortunate that Eli was available,” Stjernstrom says of signing Tomac before the 2016 season. “You’d be taking a big risk to just hope that a rider of his caliber was available.”

Now there’s a chance Cianciarulo could be racing a KX450 for the factory team in 2020. Twelve years after the recession, the rebuild is nearly complete.

“It’s different, and I think a lot of it has to do with the technical requirements of the bike, because you have to,” Stjernstrom says. “Our competitors are spending more on the technical side too. So we don’t have as many riders as we used to have, but we do still have kids in every class—Jett Reynolds and guys like that. We just feel that having our own guys is the right thing for us.”

Other teams copied Team Green’s old model and then stepped up the process, spending more and also integrating them more with the pro team. At one time, Mitch’s bikes were so good and his team so strong that he could swoop in and get a good rider whenever he wanted. But as his competitors started to improve, that grew more difficult. It’s therefore up to Kawasaki to employ all of its resources.

“They’re all under Kawasaki contracts,” Stjernstrom explains. “All of Mitch’s riders have Kawasaki contracts. Even the Team Green kids have Kawasaki contracts—same thing that Eli or Joey have, just the numbers aren’t nearly as big. Although in some cases. . . .” Seems the market really is competitive for high-end amateur talent these days.

“Adam has been part of our program for a long time, same with Forkner, Marchbanks, so now it’s working for us again,” he continues. “And it’s worked for us because we want it to work. We don’t treat them like little kids and tell them to go on their way and we’ll see them every once in a while. I’m absolutely as involved with our amateur kids as I am with this 450 supercross team.”

Kawasaki might be writing the checks, but Payton’s experience is invaluable. Stjernstrom says every decision with the amateur team comes from a four-person panel: himself, 450 team manager Dan Fahey, Team Green manager Ryan Holliday, and of course Payton.

“I don’t want to diminish the value of success at the amateur level,” Stjernstrom says. “We use the word pedigree. Does that kid have pedigree? We compare riders, even from our competitors and even from different eras, so we know how they stack up in terms of wins and championships. I think guys that are consistent winners remain consistent winners.”

(Clockwise, from left) The veteran Martin Davalos (73) got off to a rocky start this season but came through for a win in Nashville; Pro Circuit is tapping into former champion Ivan Tedesco’s vast experience to set up race bikes for the whole team, including rookie Garrett Marchbanks (61), shown here with Jordan Jarvis of WMX fame and mechanic Colton Ahrens.

(Clockwise, from left) The veteran Martin Davalos (73) got off to a rocky start this season but came through for a win in Nashville; Pro Circuit is tapping into former champion Ivan Tedesco’s vast experience to set up race bikes for the whole team, including rookie Garrett Marchbanks (61), shown here with Jordan Jarvis of WMX fame and mechanic Colton Ahrens.

Pro Circuit’s only title since 2012 is Justin Hill’s in the 2017 250SX West Region, but Payton sees much of this as an indicator of how luck can turn. He chalks up this year’s rise of Cianciarulo and Forkner to staying healthy in the off-season.

“Austin was hurt and missed time before last season,” Payton says. “He came in and tried hard, but I don’t think he was 100 percent fit. Last year Adam had a torn ACL, and that would swell up on him all the time.”

Payton knows even this hot start to the season could change quickly. His words prove too prescient, because Forkner goes down in a practice crash and twists his knee. He tries to ride the next practice but falls to the ground in pain. When I circle back to the Pro Circuit truck to check on Forkner’s status, I find Payton and ask, “What was that you said about 2014?”

He is not amused. Forkner emerges from the team truck on crutches and says, “Well, I can’t even walk, so I can’t ride.”

Forkner will now have to fight through an ACL injury to salvage the 250SX East Region Championship. There are some things Payton can’t control. For the things he can, though, he found a fix.

“Luckily, everything that I’ve come up with, they’ve pretty much liked,” he adds. “From what I see, I think it’s working.”

“He’s really good at it,” Payton says of Tedesco’s testing skills. He says the 37-year-old can still get within a second of his current riders’ lap times at the Kawasaki test track. “It’s funny, because a lot of it was small things, but when added together it made a big difference, and the riders really liked it.”

Tedesco’s role is another example of the expanded effort needed to win today. If the riders have to test, they’re not training or working on their own skills.

“These guys want to ride,” Payton says when asked why he doesn’t have his actual riders do more testing. “Only a few guys actually like testing like that, when you’re only doing a lap or two, then pulling off. Racers want to do motos.”

On the other coast, it’s hard to believe Cianciarulo has been a pro for seven years. Injuries have thwarted him, and in his comebacks, he didn’t want to lose his relentless desire or confidence. Trying to win races off the couch, though, put him on the ground too often. Now Cianciarulo, a native Floridian, has set up his operations in California so he can work with Wey and the team more closely. Wey’s mantra for Cianciarulo is to be stronger on the bike. That means working on basics over and over to improve muscle memory (and having Tedesco handling the bike surely allows them to focus a bit more too).

Wey and Payton are aware that the sport has advanced significantly over 20 years, and that they have to update their methods.

“[Adam] put so much into it at a young age, while for me, when I turned pro, it was still just a hobby,” says Wey, who enjoyed a long, respectable career. “The volume of work as a pro just shocked me. I worked hard, but mentally, I wasn’t there yet. Adam’s already seen all of that. My biggest downfall was being so hard on myself but not necessarily understanding what to do to actually be better.”

“I think Nick and I are similar in how we work,” Cianciarulo says. “I’ll put in any type of work, but I need to know why we’re doing it. We have purpose behind everything we do, and I’ve really bought into it. With Nick, I’m never just going through the motions at the track or at the gym, and that’s the kind of stuff that makes you better.”

The entire Monster Energy/Pro Circuit Kawasaki team is better because there’s an entire team working on it. Mitch Payton remains at the helm, as knowledgeable as ever. And while winning races may no longer be as simple as finding a little extra horsepower on the porting bench, Pro Circuit’s success is still owed to the man who started it all and continues to run it. Because without building all these relationships, Mitch Payton couldn’t have built anything at all.

With five wins in the first six rounds, Austin Forkner was well on his way to winning the 250SX East Region crown before a practice crash at Nashville (below) knocked him out of the race with a knee injury. As we were going to print, he was still listed as questionable for the last two rounds in East Rutherford and Las Vegas.

With five wins in the first six rounds, Austin Forkner was well on his way to winning the 250SX East Region crown before a practice crash at Nashville (below) knocked him out of the race with a knee injury. As we were going to print, he was still listed as questionable for the last two rounds in East Rutherford and Las Vegas.