PHOTOS: Spencer Owens

Opening Spread: Octopi Media/Red Bull Photo Files

PHOTOS: Spencer Owens

Opening Spread: Octopi Media/Red Bull Photo Files

At least, not until the racers—even retired ones—trained their eyes on a possible triple-quad-triple jump combo. Then it turned serious. Because these guys are racers, and even clad in costumes and riding late-model bikes, they can’t help themselves.

At least, not until the racers—even retired ones—trained their eyes on a possible triple-quad-triple jump combo. Then it turned serious. Because these guys are racers, and even clad in costumes and riding late-model bikes, they can’t help themselves.

ou saw it in Pastrana’s eyes. Someone was gonna unlock the triple-quad-triple—which, by the way, wasn’t intended to be jumped. Event creator Jeremy Malott of Red Bull even considered flattening the jumps Friday night to remove the temptation. Track builder Jason Baker convinced him that unlocking a tricky combo on a two-stroke fits the 1990s theme perfectly. So Ryan Villopoto, who retired in 2015, couldn’t help himself. He manned up for the jumps just like a championship was on the line. But this was only Friday practice. There were no fans in attendance. The run didn’t count for qualifying. Villopoto attempted the leap but clipped the landing with his back tire. Pastrana was there, on the side of the track, blipping the throttle of his 500cc two-stroke engine inside a modern Suzuki chassis. His eyes had this crazed look. If his helmet was off, you could probably have seen him foaming at the mouth. This was a rabid dog staring at his piece of meat.

ou saw it in Pastrana’s eyes. Someone was gonna unlock the triple-quad-triple—which, by the way, wasn’t intended to be jumped. Event creator Jeremy Malott of Red Bull even considered flattening the jumps Friday night to remove the temptation. Track builder Jason Baker convinced him that unlocking a tricky combo on a two-stroke fits the 1990s theme perfectly. So Ryan Villopoto, who retired in 2015, couldn’t help himself. He manned up for the jumps just like a championship was on the line. But this was only Friday practice. There were no fans in attendance. The run didn’t count for qualifying. Villopoto attempted the leap but clipped the landing with his back tire. Pastrana was there, on the side of the track, blipping the throttle of his 500cc two-stroke engine inside a modern Suzuki chassis. His eyes had this crazed look. If his helmet was off, you could probably have seen him foaming at the mouth. This was a rabid dog staring at his piece of meat.

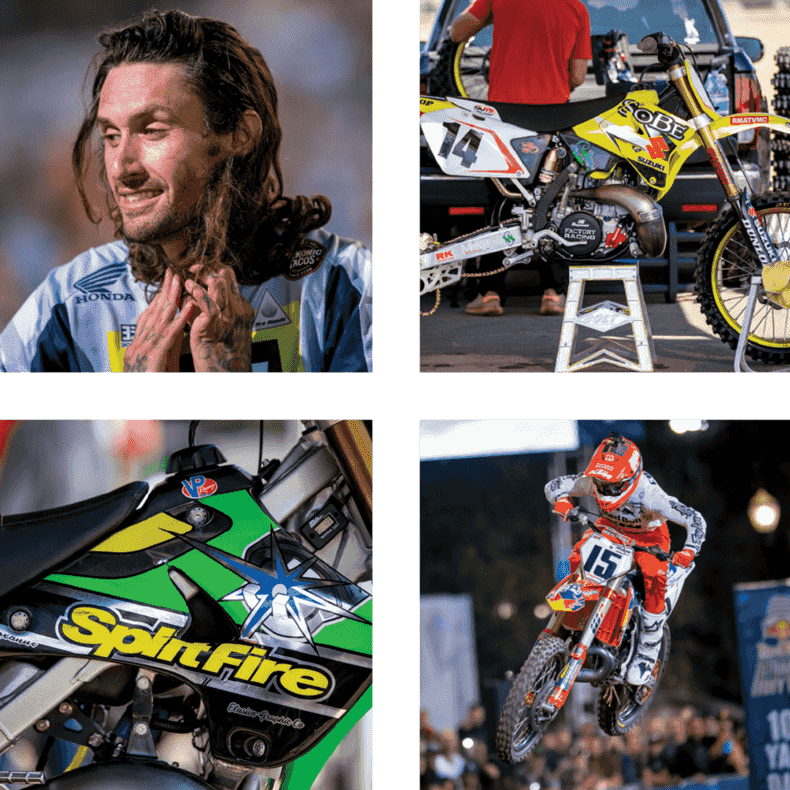

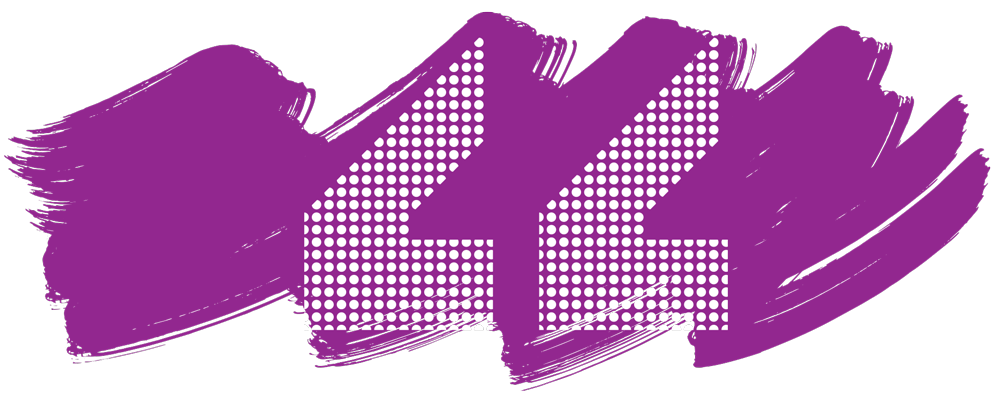

Josh Hansen, also retired from racing, jumped the first triple and then attempted the quad. He pointed the nose of his 1999 Ezra Lusk-inspired Honda CR250 sharply down. It was scary, an endo in waiting. But Hanny had done this on purpose. He pointed that nose down and aligned his bike perfectly with the backside of the quad landing, building tremendous speed for the final triple, which he nailed. It was a symmetry both violent and smooth all at once. Hanny’s rep as a super-talent was still intact. Pastrana was watching, that rabid dog growling, tugging against the leash on that big 500.

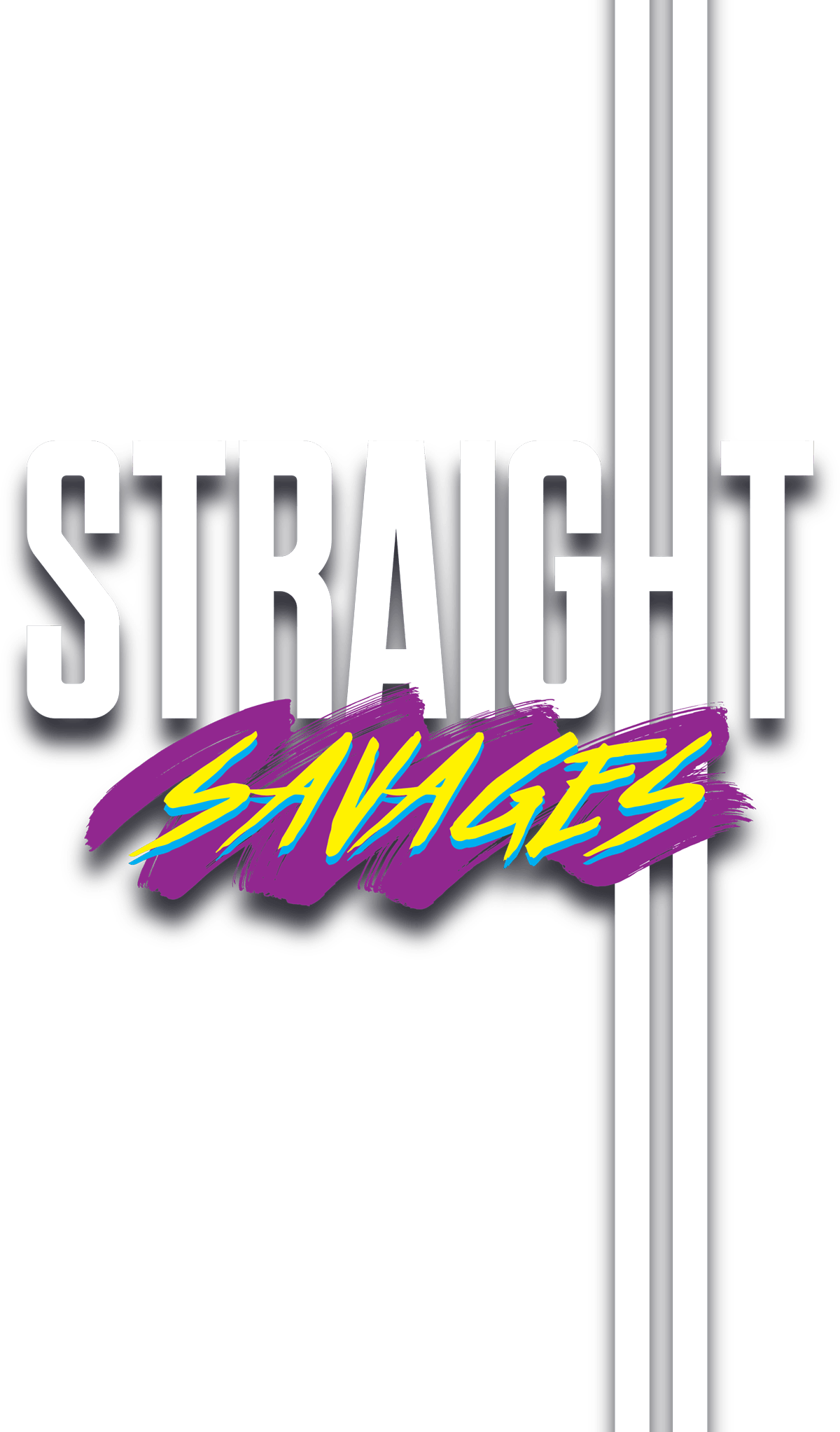

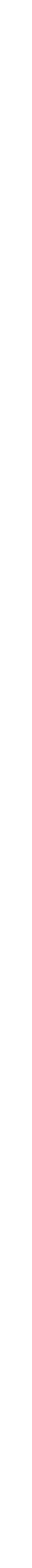

Four-time AMA Supercross Champion Villopoto tried again and came up short. Way, way short. It was the textbook definition of casing it, as his YZ250—shod with Villo-Lite graphics in tribute to Jeremy McGrath’s 2002 Bud Light Yamaha—imprinted itself on the top of the jump. The landing was disgusting. It left a frame-sized hole on the top of the jump. Villopoto immediately began grabbing at his chest and shoulder as he bounced off the track.

Come on, guys, stop this madness. It’s only Friday. “Hey, we don’t have a factory motor—we don’t even have A-kit suspension,” Villopoto’s mechanic, Mike “Schnikey” Tomlin, says. Also, the famous Pro Circuit suspension guru Jim “Bones” Bacon, who, like Villopoto, is supposed to be retired, showed up to exchange notes.

But even Bones can’t build a suspension setting that helps when a bike lands frame-first on a jump. The weekend would become a competition both on the track and off, each rider trying to top the other’s tale of being less prepared, with the bike that’s least ready for primetime.

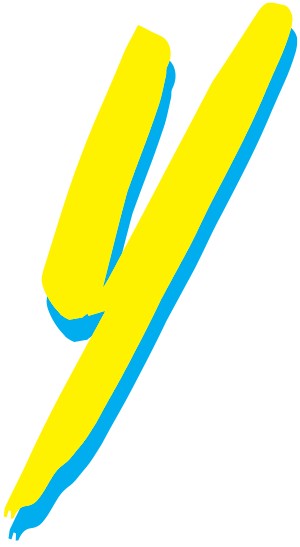

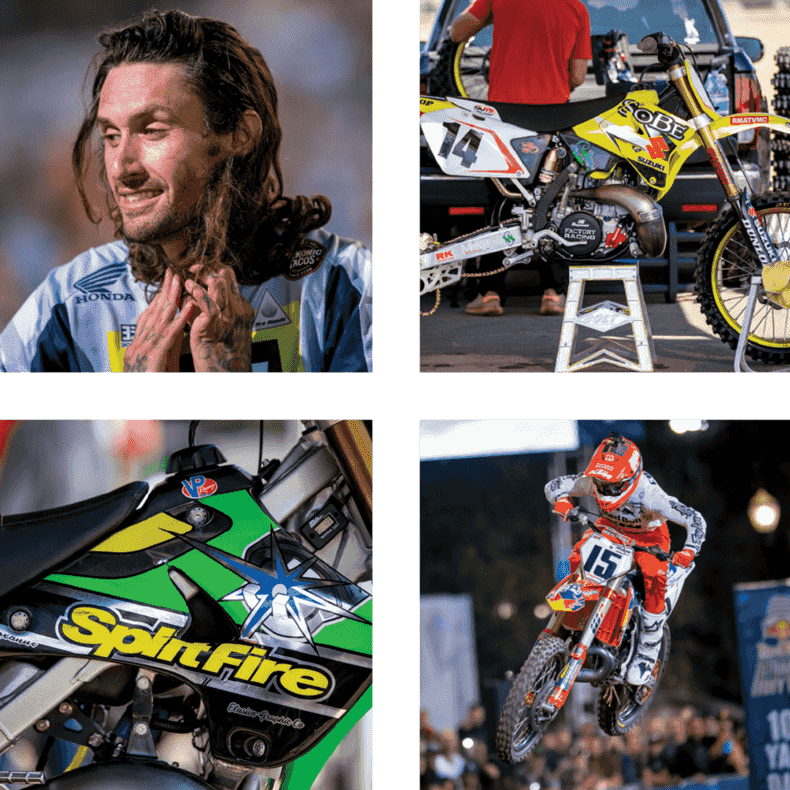

Really, no one had a bike less suited for this than Tyler Bowers. He rode a 1991 Kawasaki KX500 that he’d bought on Craigslist and built in his garage with buddies while drinking beer. He called it The Unit. Bowers is a self-professed “bad mechanic,” and KX500s were never designed for supercross. He couldn’t even find anyone crazy enough to race him until Pastrana, of course, took the challenge. Bowers asked Malott if he should maybe let up to make it close against Pastrana, who hasn’t raced in over a decade, which then only set Pastrana’s competitive instincts ablaze. But at least Pastrana had an old motor in a new frame.

Within a few minutes, Villopoto’s pain subsided enough, and he kicked his YZ back to life and headed back to take another practice run. Then came Bowers, ambling down the Straight Rhythm track, the low revving five-hundy sound matched with suspension and a frame that looked Cadillac soft. Bowers’ modern riding skills overcame the bike’s misapplication. He lofted the triple-quad-triple perfectly. The Bear approached the section more like The Ballerina, and with good reason. Tyler said his 500 doesn’t have a lot of low-end power, but when it suddenly hits in the mid-range, you can easily shoot 20 feet farther than intended. And if he were to mistime his jump and clip the landing like Villopoto? He figured the bike would snap in half.

Now it was do-or-die time for Pastrana, which is the moment he lives for. So he did . . . a backflip into the rhythm section, then pulled the triple-quad, and, for good measure, heel-clicked the final triple. Then he followed that with a series of fist pumps. All 30 people on the fence were watching, amazed.

“I felt like there was some serious stuff going on,” said Cooper Webb, the current AMA Supercross Champion.

erhaps no one worked harder than Michael Leib, who scored second place in the 125 class behind Joey lot of the retro gear via his company, Canvas, which specializes in custom looks. That included AJ Catanzaro’s dead-on Pastrana tribute look, and also Pastrana’s own gear, which was designed by AXO’s legendary nineties designer Kenny Stafford. Canvas made Stafford’s greatest hits come to life. Leib adopted a Team Honda Ernesto Fonseca look for himself, except his logos said MLD, for Mike Leib Designs, instead of TLD for Troy Lee Designs. The only problem was that running the Fonseca look required a Honda CR125, which is not even close against modern KTMs. Leib said he “brought a knife to a gunfight,” but he still took second and looked good doing it.

erhaps no one worked harder than Michael Leib, who scored second place in the 125 class behind Joey lot of the retro gear via his company, Canvas, which specializes in custom looks. That included AJ Catanzaro’s dead-on Pastrana tribute look, and also Pastrana’s own gear, which was designed by AXO’s legendary nineties designer Kenny Stafford. Canvas made Stafford’s greatest hits come to life. Leib adopted a Team Honda Ernesto Fonseca look for himself, except his logos said MLD, for Mike Leib Designs, instead of TLD for Troy Lee Designs. The only problem was that running the Fonseca look required a Honda CR125, which is not even close against modern KTMs. Leib said he “brought a knife to a gunfight,” but he still took second and looked good doing it.

Roczen probably had the coolest bike of all: the actual factory Honda CR250R that Jeremy McGrath raced (after coming out of retirement, natch) at the ’06 Phoenix Supercross. That night, MC snagged the holeshot on his two-stroke and pulled a nac-nac over the first triple while leading. It would be the last holeshot and main-event lap led for a two-stroke in AMA Supercross competition, as the King himself switched to a 450 the next weekend.

Honda’s graphics backer Throttle Jockey put in painstaking efforts to make the ’06 aluminum-framed CR look like an early-nineties replica. Honda even found a 1994 number plate to strap atop a set of modern 450 forks. It’s key to understand that Roczen was born in 1994. He did a throwback video for Fox a few years ago where he rode McGrath’s 1996 CR250R (which, famously, ran a 1993 frame), but Kenny is far from a two-stroke expert. Cooper Webb, born in 1995, was at one point the poster child for Honda’s CRF150F four-stroke mini. His lack of two-stroke time showed, as he never quite looked comfortable on his KTM 250 SX. Jason Anderson, who had just spent a month grinding sand laps on a 450 in Europe, pulled out of the event after practicing on Friday. But Anderson hadn’t raced on a supercross track since January, and on his very first run, the ’18 AMA Supercross Champion blitzed the whoops with ease. Riders have high standards.

“I should have treated it more like a fun race,” Roczen admitted after winning the event. Roczen said the Straight Rhythm track was faster than the Honda test track—which has turns—and his suspension felt too soft. He started getting perfectionist and picky with his 13-year-old bike. Honda tech Lars Lindstrom was seen—and heard—making multiple jetting runs over in the back of the Pomona Fairgrounds facility. However, Roczen and most of his fellow riders admitted they didn’t know the difference between bad jetting and just the standard response of a carbureted two-stroke.

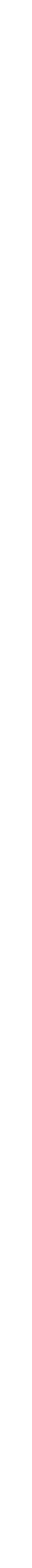

The racer came out in Roczen, but he wanted no part of the triple-quad-triple and feared facing Hansen, who had it handled no problem. Once, Hansen muffed the last triple, thus giving Roczen the window he needed. They raced again, and this time Hansen nailed the section.

“He was so far ahead of me,” Roczen said. “I’m like, ‘There’s no way I’m going to catch him again.’ So then I just started scrubbing the shit out of the walls. It might not look spectacular, but I was leaning the bike over at the very bottom of the takeoff. I probably scraped my side panel on the freaking dirt! But I had to make up a lot of time. Then I just held it wide open in the whoops.” Roczen and Hansen set the fastest times of the event in their final battle, Roczen winning by a few hundredths of a second.

Roczen beat Troy Lee Designs/Red Bull KTM newcomer Brandon Hartranft in the final. (Hartranft had actual TLD gear, designed to look like Evel Knievel’s.) After the race, Roczen’s pit area was mobbed with fans. Amateur graduates Pierce Brown, who beat Webb, and Parker Mashburn, who beat Villopoto, rolled up, not recognized by a single spectator. Maybe they had made names for themselves, but their faces are still unknown.

That was the idea. This was a costume party with retro two-strokes. The connection to actual racing was left intentionally fuzzy, but deep down, it was the same as always: Leib wished he’d had a little more motor in the 125 class, Bowers had to go all-out to beat Pastrana, and Roczen, who should have had fun with it, had to scrub and blitz with all of his might to win. Because no matter what the setting, the bikes, or the costume, that’s straight-up all that racers really want to do.

Roczen beat Troy Lee Designs/Red Bull KTM newcomer Brandon Hartranft in the final. (Hartranft had actual TLD gear, designed to look like Evel Knievel’s.) After the race, Roczen’s pit area was mobbed with fans. Amateur graduates Pierce Brown, who beat Webb, and Parker Mashburn, who beat Villopoto, rolled up, not recognized by a single spectator. Maybe they had made names for themselves, but their faces are still unknown.

That was the idea. This was a costume party with retro two-strokes. The connection to actual racing was left intentionally fuzzy, but deep down, it was the same as always: Leib wished he’d had a little more motor in the 125 class, Bowers had to go all-out to beat Pastrana, and Roczen, who should have had fun with it, had to scrub and blitz with all of his might to win. Because no matter what the setting, the bikes, or the costume, that’s straight-up all that racers really want to do.